Warning: this is a rather sad unpleasant story.

Thomas Bradbury was a very typical and quite unremarkable example of my Victorian farmer ancestors. Born on 21 December 1820, the youngest of eleven children and the third surviving son, Thomas had been fortunate to secure his own tenancy of a twenty-acre farm within walking distance from where he was born. He married a local girl, Jane Teal, on 29 November 1845. Six healthy children arrived at regular intervals and the family continued to farm at Woodmanwray until Thomas died, aged fifty-eight, on 29 March 1879. Thomas’s gravestone in the Providence United Reformed Churchyard at Dacre had given me his date of death. What else was there left for me to learn? Nonetheless, I added his death certificate to my general registry office shopping basket before moving on to other, more interesting ancestors.

A month later my sister called. A pupil at her school had accidentally ripped the birth certificate belonging to a colleague’s son. Might I be able to help her source a replacement? (There are, it seems, practical benefits to having a family history geek as a sister). It was back to the general registry office website. I took the opportunity to add the rest of my shopping basket to the order and Thomas’s death certificate was on its way.

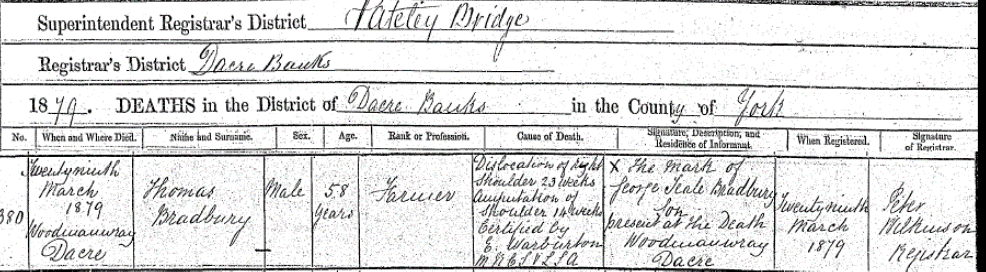

And right there, under cause of death, was Thomas’s story.

Agriculture still has the worst rate of worker fatal injury (per 100,000) of all the main industry sectors, with the annual average rate over the last five years [to 2020/2021] around twenty times as high as the all-industry rate. At primary school we watched horrifying educational videos of children crushed by machinery or drowning in slurry. Yet friends were still beset by agricultural injury (including one who lost fingers) and I particularly remember the vividly coloured bruises Grandpy received from a tussle with an unruly sheep. Stepping back a hundred years or agricultural accidents were much, much more common and medical assistance much, much less effective.

It was mid-October 1878 when Thomas dislocated his right shoulder. Perhaps he had a run-in with a cow or fell from a roof he was fixing, maybe he twisted his arm trying to manoeuvre a too-heavy stack of straw or simply got caught under an overturned wagon. A common enough occurrence, the initial accident didn’t leave a written record. Whatever the cause it would have been painful and debilitating, the sole positive being that of his family: adult children to run the farm and a wife to provide nursing care.

The dislocation must have resulted in disruption of the blood flow to his right arm. Gradually over the following couple of months, Thomas would have seen the tissue in his right arm blacken and die. Whilst it is possible that numbness would have overtaken the pain, the foul smell of infected gangrene could not have been ignored and at some point, Thomas would have called on the services of the local doctor and Medical Officer of Health for Pateley Bridge, Edward Warburton MCRS, LSA.

Thomas was fortunate to have such a qualified doctor within calling distance. Edward Warburton’s father, Joseph, had first arrived in Pateley Bridge in 1807 to act as an assistant to Dr Strother. In 1815 the law changed requiring new doctors to be licenced and whilst in earlier years Joseph’s apprenticeship and family connections would have been sufficient, he was now required to qualify. Joseph headed off to London where he studied under the esteemed Mr R. C. Headington (later a president of the Royal College of Physicians) qualifying as a surgeon-apothecary in 1816 before returning to Pateley Bridge. By 1834 he had attracted a young John Snow to act as his assistant, the same Dr John Snow who is considered to be the founding father of both modern epidemiology and the scientific use of anaesthesia. Such was Dr Snow’s reputation that it was he who administered chloroform to Queen Victoria during the delivery of two of her children. Edward himself was apprenticed to his father and qualified through practice at Leeds Royal Infirmary in 1846. Snow remained a long-standing friend of the Warburtons, and Edward would likely have been far more knowledgeable about anaesthesia than many of his rural counterparts. There have been studies too, which demonstrate that the average mortality rate after amputation in cottage hospitals was somewhat lower than that in large city institutions but it still hovered around one in five. Surprisingly in the late 1800s, living this part of rural Yorkshire put Thomas in the best possible hands.

Just before Christmas, Thomas underwent surgery. By 1878, anaesthetics were being used effectively and, more critically, the principles of antiseptic surgery were just starting to be accepted. Thomas may have felt hopeful. He seems to have escaped the initial dangers of shock, haemorrhage, and exhaustion. There was no early onset of septicaemia. The new growth of early spring arrived. Snowdrops were replaced by wild daffodils and garlic. However, amputation also comes with an increased risk of heart attack and deep vein thrombosis, or, more likely, if gangrene had spread beyond his arm, it would have continued to attack vital organs. In the end, nearly six months after the initial accident and three months after his amputation, Thomas died at home in Woodmanwray, his family by his side, his cause of death certified by his surgeon.

Thomas & Jane’s eldest daughter, Amelia, married Michael Houseman. Their son, Jesse was the father of Mary Houseman, my Grandma. Grandma loved to tell a death story, but this was just a generation too far back for it to be part of the tales she told and a reminder of how important it is to track down every document.

Brief biographical details of Jane Teal and Thomas Bradbury

Jane would have been born between 17 January & 2 March 1823 at Holm House (possibly Lower Holme House according to later census records). She was the daughter of Amelia Layfield and George Teal and had five other siblings.

Jane & Layfield were twins. We don’t know whether Jane was born first, but it was Layfield, her twin brother who is listed first in the baptism record on 2 March 1823. It seems she may have been the strongest as Layfield died in November 1826 aged just three years old.

Jane’s mother died in May 1830 when Jane was seven years old.

By the time she was 18, Jane was working as a farm servant at How Gill, Stonebeck Up about 8 miles further up the valley from her family, but in close proximity to her brother William.

Thomas was born a little earlier, on 21 December 1820, the youngest of the ten children of Catherine King & Charles Bradbury. By 1841, the family had moved to Fountains Earth which bordered Stonebeck Up. Thomas’s widowed sister, Catherine, and her son, were living next door. Jane & Thomas likely met around this time.

The pair married on 29 November 1845 in Ripon cathedral. By this time, both were living in Dacre and Thomas was described as a farmer, Jane as a servant. Jane was illiterate, but Thomas could write. I wonder if Thomas had finally found a small farm of his own and Jane had taken work nearby or had even moved to be with him. It seems odd that they got married in Ripon if they had both already moved to Dacre. But equally odd they didn’t get married in Middlesmoor if they hadn’t. Dacre church had been built in 1837.

The couple had six children representing many of the family names. Charles & Catherine (paternal grandparents), Amelia & George (maternal grandparents), Teal & Layfield as middle names (Jane & her mother’s maiden names).

Charles (1848 – 1925), Amelia (1848 – 1931), George Teal (1850 – 1898), John Layfield (1853 – 1922), Catherine (1857 – 1882), William (1860 – 1926). Catherine & her husband died within six months of each other. All the children married and had children of their own.

The couple lived the remainder of their adult lives on a 20 acre farm at Woodmanwray towards the north end of Dacre. Woodmanwray old chapel, where perhaps they worshipped is now available to rent on Airbnb. There’s a lovely description of the farm when it was put up for sale on 30 June 1885. At the time the land was still farmed by Jane & Thomas’s son, George Teal.

“All that compact FARM, with the recently stone-built House, together with the Plantation, Garden, Barn, Stable, Cowhouses, Piggeries and other outbuildings and 9 CLOSES OF LAND, with the allotments or enclosures of grass and unbroken-up lands…..There is a never failing stream of water running through the premises…..The situation is healthy, well sheltered, commands pleasing views of the neighbourhood and is very suitable for residential purposes…”

Thomas died on 29 March 1879. Jane continued to live at Woodmanwray and expanded the farm to 35 acres with the help of her children. She died, of heart disease and exhaustion on 16 January 1891, aged just 67. They are both buried at Providence Congregational Church at Dacre.

With particular thanks to my twitter #AncestryHour friends who helped me broaden the research, to Spence Galbraith who studied Dr John Snow and made his research on the Warburtons available online and lastly to Thomas Bradbury, my great, great, great Grandfather for enduring the long months of pain whether stoically or not.