Many years ago I bought a print of this painting. It’s Leeds, not Mirfield and painted a little late (1893) for our story but so evocative of industrial Yorkshire.

Unusually amongst our ancestors, Elizabeth Schofield & Thomas Moody’s lives did not focus on a single farm, house or even a village for their family was not built on land, but rather around water, specifically the Calder & Hebble Navigation. The journey along the canal from Mirfield to Horbury Bridge via Thornhill Lees is under seven miles. It takes a couple of hours to travel it by narrowboat and yet this short stretch of waterway spans Elizabeth & Thomas’s lives.

The canal also helped to obscure their beginnings, particularly those of Elizabeth. Watermen had a tendency not to complete census forms whilst on the move, which was often if they were to make a living. Elizabeth remains unaccounted for in the 1841 census (and I am uncertain about that of 1851) and Thomas in those for 1851 & 1871. Several of their children’s baptisms and burials remain missing and Elizabeth’s father, William, is currently without both parents and a date of death. Nonetheless I now feel sufficiently confident in the evidence to be able to tell the story of Elizabeth & Thomas, my 3xG grandparents through their son, Ernest William, father of Marion, Nana’s mother.

Elizabeth was born first, baptised on 9 December 1832, the likely first child of Margaret Robshaw & William Scho[le]field. The family were living at Ledgard Bridge at the time, quite possibly on the barge itself. At some point between the birth of Elizabeth’s siblings William (1834) & Sarah (1839), the family appear to have relocated to Thornhill Lees although the whole family was on the move and unrecorded on the night of the 1841 census.

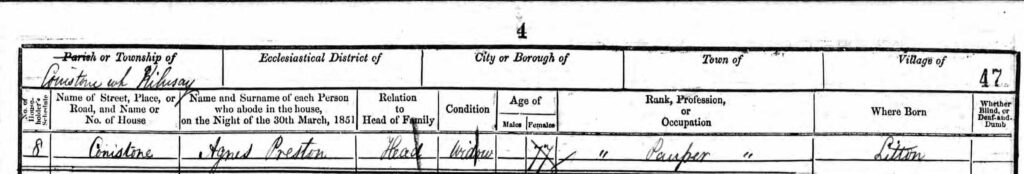

Elizabeth is difficult to pin down in the 1851 census, but after eliminating all the other Elizabeth Scho[le]fields born in Mirfield the only one left is a visitor of a widow called Susan Wooler or Woller in Cleckheaton. If this is indeed our Elizabeth, there’s a potential familial & religious connection for further research and it also tells us she was working in a woollen mill a trade her sisters were also to follow.

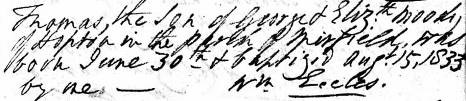

Thomas was also an eldest child, born on 30 June 1833 in the village of Horton. His parents, Elizabeth Lee & George Moody, went on to have six more children, all of whom survived into adulthood. The Moody family were staunch Presbyterians and maintained an ongoing link with Hopton Independent Chapel where Thomas was baptised.

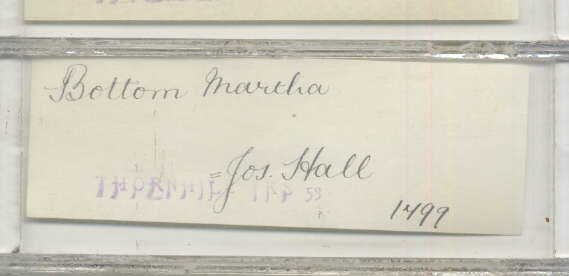

George Moody, Thomas’s father, was a woodsman and built up a successful timber business. His youngest son, William Henry, or Harry ran a joinery and undertaking business in Upper Hopton building on his father’s trade. His next youngest son, John, also, in a way, entered his father’s trade, apparently of stealing three loads of timber in 1899 and sentenced to 21 days imprisonment in HMP Wakefield (although I should note that there were other John Moodys in the area at the time).

Why, then, did Thomas take to the canals? It is rare, in my experience, for eldest sons not to follow their father’s trade. The charitable explanation is that George had set his son up in logistics as a useful compliment to the timber trade, but I just don’t buy that. In my view Thomas’s career choice was either the cause of a father/son falling out or a result of one as there is no evidence that Thomas had anything to do with Moodys of Hopton in later life, no marriage witnesses nor visitors on census returns, no presbyterian religion and certainly no evidence of financial support.

Thomas is nowhere to been found in 1851, so on a barge I would guess.

Elizabeth & Thomas were married at St Michael’s & All Angels at Thornhill on 7 September 1856. At the time both were living on Lees Moor which aligns with the 1861 census above. Children quickly followed, Mercy just a couple of months after they married, Jane in 1858, Emma in 1861, George in 1863 and Lee in 1866. Lots of little helpers.

In the mid-1800s a canal boat would absorb the whole family. Men, women and children worked them and those same men, women & children lived in them. When transporting a load, the seventeen-hour days would have required all those able to lead the horse, steer the tiller and unload the cargo. Those who were too young to manage the heavy work would be keeping a close watch over their younger, toddler, siblings to make sure they didn’t get in the way of the work or even fall overboard. Living accommodation was cramped and squalid with limited facilities to wash or even to cook. Educational opportunities were non-existent and although Thomas was literate, none of the older Moody children were. Canal boat people were often misrepresented by outsiders, a community in need of civilisation.

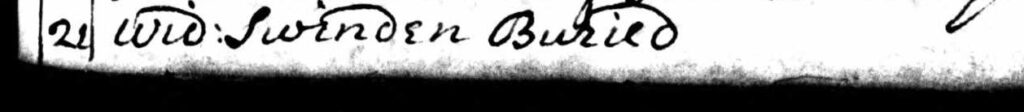

Disease was rife on the canals: it was even suspected that cholera flowed down the channels from cities out to smaller towns. When ten-year-old Mercy & six-year-old Emma died within four weeks of each other in the summer of 1867, it was time for the Moodies to make a change to their way of life. The family moved to Horbury Bridge and into an onshore home. Four more children followed: Mercy in 1869, Tom in 1872, William in 1874 and then finally, twenty years after her first child, Elizabeth gave birth to her last, Ernest William, in 1876 whose middle name gave away her next to last child, William, had not survived infancy.

George and Lee both followed their father onto the waterways and Jane, too, married a waterman but the younger boys, Tom & Ernest went into millwork. By the time they were of age the golden era of the canals was being supplanted by rail for valuable goods at least. Designed as they were, the canals still retained a critical role for transporting coal and other heavy goods direct from mine to factory gate. Perhaps though, their choice of career was influenced by what happened to their elder brother Lee. I’ve not been able to find out any details but by 1901 Lee, aged 34, was blind.

Working in a mill seems also to have helped the boys’ marriage prospects as both Tom & Ernest married whereas George & Lee did not. Mercy too, was to remain a spinster, seemingly destined to stay at home to look after her aging parents and blind brother.

Thomas died in March 1901 aged 67 and Elizabeth in December 1911, aged 79. With their burial in Thornhill churchyard our direct connection to the water came to an end although not our connection to Horbury for Ernest had stayed in Horbury when he married, as did his daughter, my Aunty Edie, whom we used to visit when I was a child. It was not until she died in 1984 that we lost our final connection to the Calder & Hebble Navigation.

With much gratitude to all those who worked on our canals transporting goods to enable industry and who were often misunderstood. Thanks too, to Elizabeth Schofield & Thomas Moody for providing me with an excuse to gain a deeper understanding of these lives.