For the first 23 years of her life, Mary Ann (my great, great, great grandmother) was the daughter of Richard Gill, tailor. In 1859 she married and became Mrs William Reynard, the blacksmith’s wife. These are typical of the identities ascribed to our ancestor mothers. We track the women through their fathers, their husbands and their children and then we pass by. What makes this story different was one short reference to a spice loaf, baked regularly by Mary Ann in her kitchen, a glimpse of a woman behind the men.

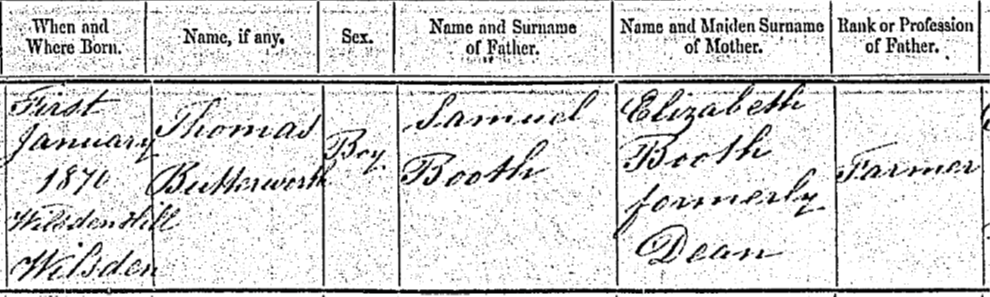

Mary Ann was born between 7 June & 13 July 1836, the sixth of Maria (nee Spence) and Richard Gill’s eleven children. We can assume she was baptised at Fewston church, like her siblings, although there is no record of this. Instead, her date of birth is derived from her age on later records.

The Gill family lived at Bland Hill in the village of Norwood close to the beautiful river Washburn in Yorkshire. It’s where I went to primary school, regularly passing R Gill & Sons, Joiners, without any inkling of our potential relationship.

Richard was a tailor, likely sourcing linen, worsted or cotton from one of several mills sited along the river Washburn. The Gills were relatively prosperous. There was work enough for at least three of the sons to join the family business and a small farm to retire to. Richard was perhaps also a man very much aware of his social status even beyond death. Richard died in 1883 aged 76. His grave in Fewston churchyard is marked with a large granite obelisk instead of a simple slab of york stone like most of the others. Perhaps most fascinatingly of all, when his grave was excavated in 2009/2010 as part of the building of the Washburn heritage centre, Richard was found to have been buried in his socks and wig, surely the sign of a man with pride.

The Reynard family lived on a farm in the nearby village of Hampsthwaite. William (born in 1833) was three years older than Mary Ann and it is quite possible they knew each other from an early age. As the second of three sons, William had little chance of inheriting the family farm and so, by the age of 18, he was working as farm servant at a large farm in Allerton. At some point over the next few years, he trained to be a blacksmith and moved to Osmotherly, over 40 miles away.

Whether Mary Ann & William had stayed in touch over that period, or whether William bumped into a newly grown up Mary Ann on a trip back to see his family, it was at this point that the 27-year-old William felt sufficiently secure in his station to approach Richard Gill for Mary Ann’s hand. They married in Otley on 13 July 1859.

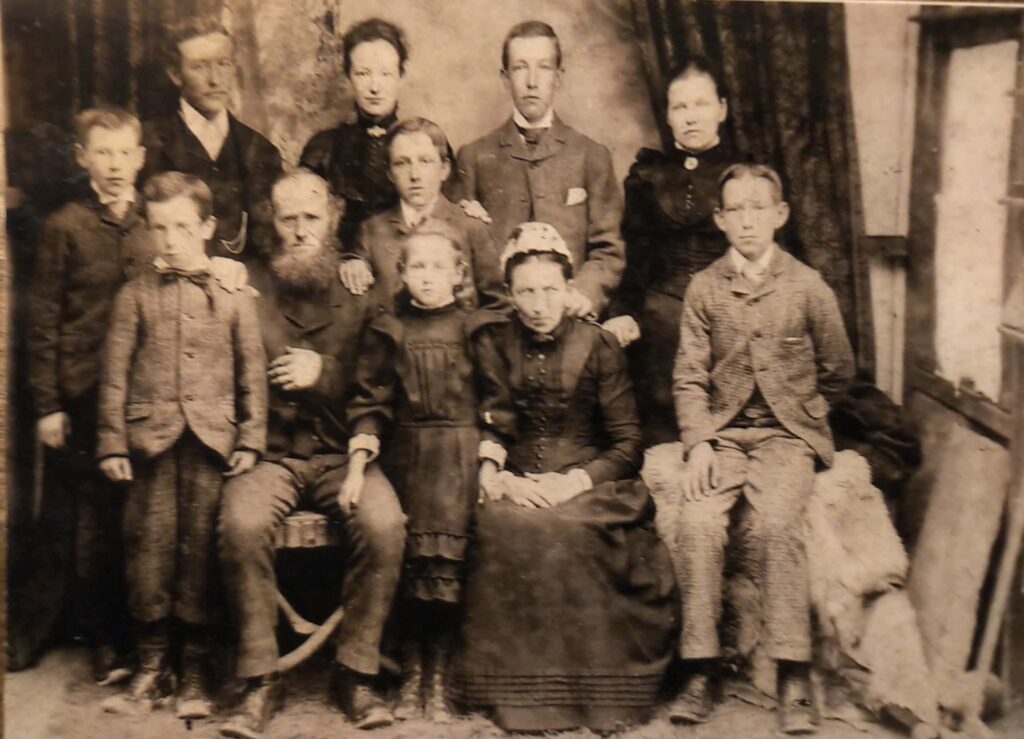

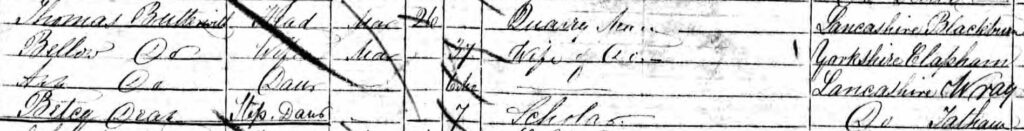

Children quickly followed. Sarah Ellen (1860), Maria, my great, great, grandmother (1861), and Annie (1865). Then a move to the village of Topcliffe, perhaps to take over a more prosperous blacksmiths business. Mary was born in 1867, Hannah in 1871, John William in 1873 and finally George Gill in 1879. They were a close family – I’ve inherited a great deal of warm correspondence between the children in later years although, sadly, none with or about their mother, Mary Ann. Maria’s family album contains many pictures of the family.

A daughter, a wife and a mother. Then I chanced upon “Topcliffe. A history by Mary Decima Watson” written in 1970 and here was my glimpse into Mary Ann herself.

“It was a custom at the turn of the century for the tradesmen of the town to send out their accounts once per year. The joiners, the sadlers, the shoemakers and the village blacksmith. The farmers sold their livestock for the year, and would then settle their accounts with the tradesmen. The village blacksmith’s wife had her own special custom, she made a very nice spice loaf, so that when the farmers called to pay their accounts to Mr Reynard, the blacksmith, she would cut a piece of this loaf for the farmers, or anyone paying their accounts to eat while her husband attended to the business side.”

An excellent baker, a custom-setter and, I like to think, a thoughtful and generous woman.

Sadly, Mary Ann died of influenza and jaundice on 2 April 1895, aged just 58. Dead, but not forgotten, thanks to that spice loaf.

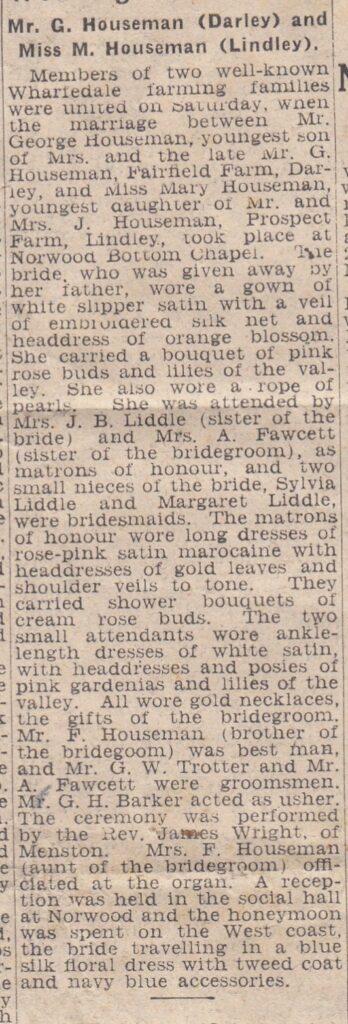

Mary Ann was mother of Maria Reynard who was mother of Hilda Mary Scott who was mother of my maternal Grandma, Mary Houseman.

With much gratitude to my Mary Ann Gill for her spice loaf, my friend Andrea for the photo of the memorial, the Washburn heritage centre for their work on the graves at Fewston and thanks also to Amy Johnson Crow whose 52 ancestors in 52 weeks challenge encouraged me to publish this series of stories.