We begin our family history journey at the end. There are many logical reasons for this, for after all, what would be the beginning? The generationally oldest ancestors? I believe I know something about eighteen 12x great grandparents who lived in the 1500s but far from enough to make their life interesting and what about the other 8,174 of them (endogamy aside)? DNA? Mine simply supports what I already know – my ancestors are mostly from Yorkshire. However, there is one other angle, that of surnames which can provide an insight into ancestors much further back than we will ever be able to prove.

In this article, the numbers born refer to the period from the start of civil registration, currently transcribed on freebmd (1837 – 1992 approx). The counts for the first seven surnames were taken on 3 August 2022, for more distant ancestors on 29 November 2022.

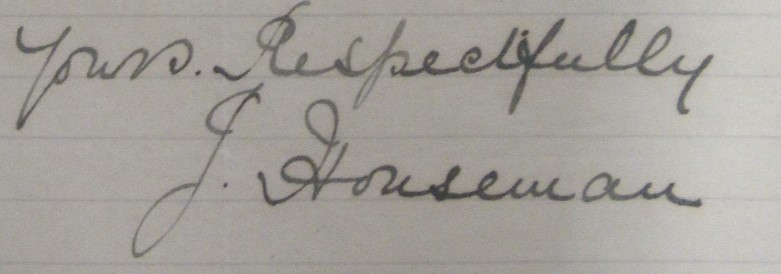

Born a Houseman, like my Grandma, I plan to die as one. Although I’m resorting to changing my name back by deed poll whilst my Grandma just married a Houseman. As the subtitle to my website notes “it’s who I am.” It is, though, only my second favourite surname. Largely, I think, because it’s already been well-researched and I am forever grateful to Gary Houseman who proved the link between my two paternal grandparents.

Whilst this surname is believed to originate from an occupation, from someone working at or associated with the local “great” house, it is relatively uncommon and highly geographically concentrated. 43% of the 2,651 Housemans born in England & Wales between 1837 and 1992 (as counted on 3 August 2022) were born in Yorkshire counties and of these there is only one branch who are not directly related. I was delighted to find that the one family in Yorkshire who are not related by blood can still be connected into my tree as William Shaw Houseman (b. 1848) who’s father, Robert, was born in London, married Hannah Smith, who’s mother was a Houseman!

By contrast, I’ve never felt the same connection to my mother’s maiden name. It crops up too often for me to be sure I’ve found the right family. There’s even a shoe store which carries the name. Our Barretts had the audacity to originate from Gloucestershire and it’s Norman in origin. Sorry Grandpy, I love you, but it’s not a surname that holds my attention.

Nana’s birth name.

Many years ago I spotted a beautiful seventeenth century wooden tray painted with the names of a Booth family. £400 was an awful lot of money but I was severely tempted, convinced the family would be related somehow. Whilst I still hold a slight sense of regret the chances that the tray family were in anyway related is slim to non-existent for there were nearly 50x as many Booths born as Housemans.

Booth is considered to be a northern name (over a quarter of those registered births were in Yorkshire) originating from the old Danish word “bōth” meaning a temporary shelter such as a cattle-herdsman’s hut. We were cattle keepers, probably the most appropriate of our surnames throughout my paper history. It also accounts for the 2% of Swedish & Danish ancestry in my Mum’s DNA profile.

Booth is also one of the two surnames I planned to use if I was ever to write under a pen name, which leads me onto….

Nana’s mother’s birth name and the other pen name I would choose.

From the Middle English mody meaning ‘proud, haughty, angry, fierce, bold, brave, or rash’ not grumpy as it is now.

I broke freebmd trying to work out what percentage of people had been born in Yorkshire, but in the 2021 census, Yorkshire was home to about 9% of the population of England & Wales so essentially anything over 10% represents a northern bias and Moody, at 14% is no exception.

But as for Moodys being proud & haughty? This was the most unassuming branch of our family tree. We’d obviously not inherited those genes.

Grandpy’s mother’s birth name.

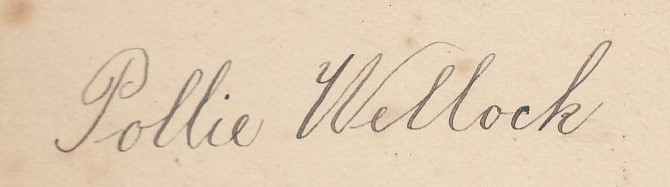

I love the Wellock surname. Most recently it’s enabled a wonderful Canadian adventure. Every Wellock alive today can be traced back to just two men. They are either descendants of Henry (born in the late 1500s in Kirby Malham) or of Robert (b. c. 1546 in Linton in Craven). The two are undoubtably related but I am always disappointed when a Wellock is descended from Henry.

Common thinking is that Wellock is a derivation of de Wheelock suggesting Norman ancestry, but given that the Wellock (or Walock) name is only held by those from Craven, Yorkshire, my interest stops there.

Grandma’s mother’s birth name.

Ultimately it’s a man from Scotland. Which could mean anything. Weirdly, my Mum’s DNA contains a lot of unexplained Scottish DNA whilst my paternal Uncle’s contains none. It’s also the most common surname amongst my great grandparents. Combine it with John and you’ve got a genealogical nightmare. So I just feel grateful that I’ve been able to trace this line as far back as my 6x great grandfather, John Scott, born in the early to mid 1700s in Branton Green, North Yorkshire.

Grandad’s mother’s birth name.

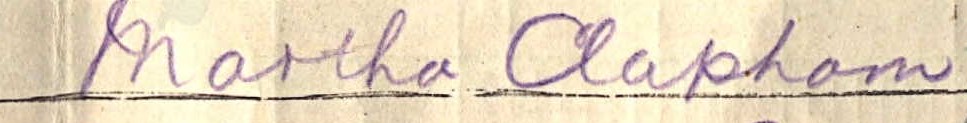

The last of my great grandparents surnames is slowly gaining my attention. Growing up there were a lot of Claphams and I thought it must be a common name. But there were under 10,000 of them born between 1837 and 1992 and of those, over 40% were born in Yorkshire. Which explains why there were a lot of them about when I was growing up.

More interestingly (for me), I have Claphams on my maternal side too – my 5x great grandmother, Elizabeth Clapham was born in Lawkland about three miles from the village of Clapham.

Given that Clapham is believed to originate from the name of a village that could suggest a connection for whilst there are Clapham villages and (different) family branches originating as far away as Bedfordshire, Surrey, Sussex and even Devon, my Grandad’s mother’s family had been slowly tracking south and east away from the original Clapham village.

Could this be the elusive connection between my Mum & my Dad’s family trees?

Earlier generations

Going back to my 3xG grandparents adds a further twenty-four surnames. It seems I’m unlikely to ever find a familial connection to my friends Sarah Walker & Helen Cooper (being the two most popular surnames in my tree with over 300,000 of each of them born). There were fullers and coopers in almost every village from which these surnames derive.

There are some though which will be worthy of further exploration.

- Stansfield, Furniss and Hinchcliffe are all relatively rare. They are locational surnames recognising people from Stansfield (near Todmorden), Furness (Cumberland) and Hinchliff (near Holmfirth) so it is not surprising that around 50% of these births were in Yorkshire. Each one might give me a hint as to where the families originated from. Each also has a number of different variants and the exact spelling could be useful in tracing my line.

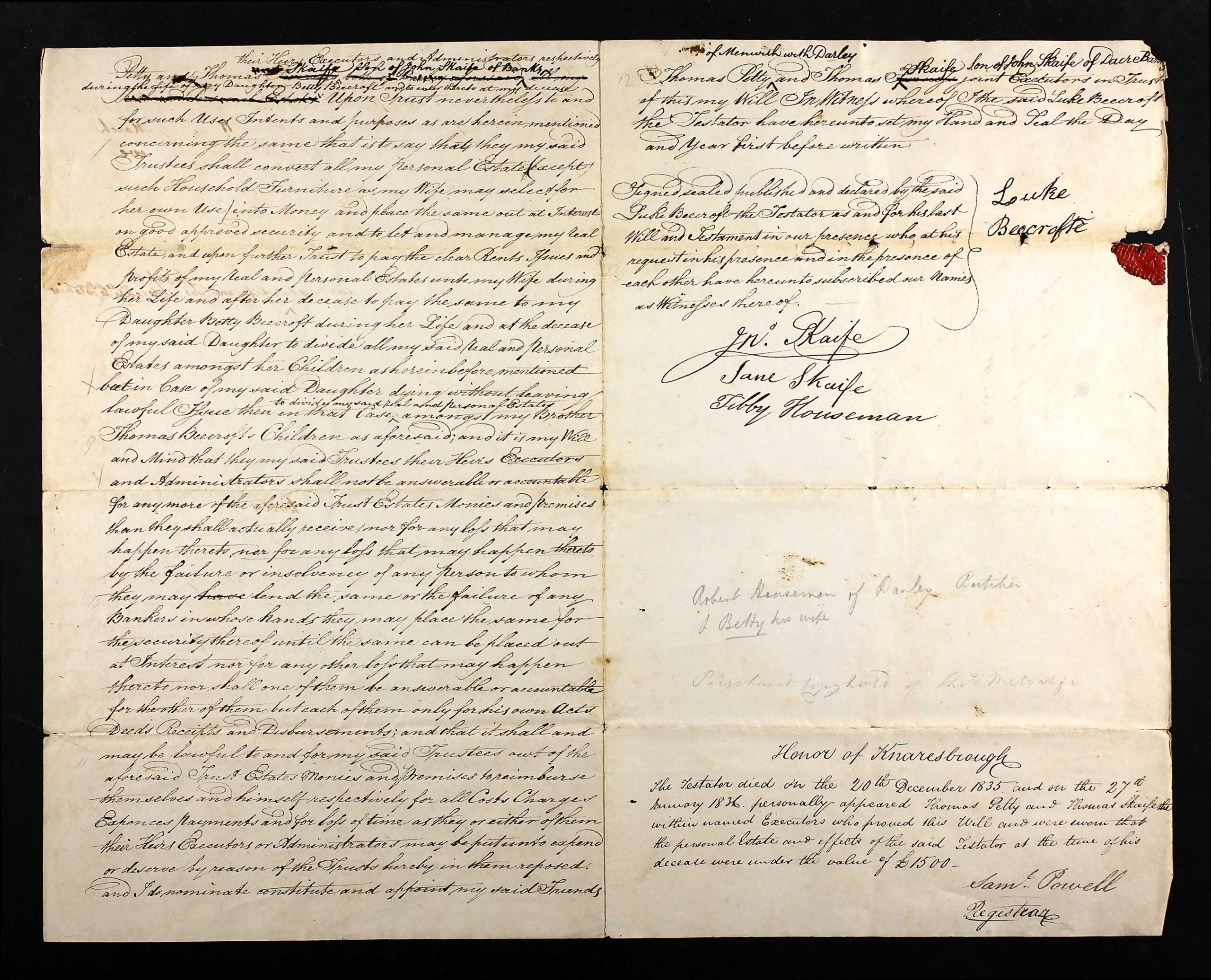

- I grew up surrounded by Beecrofts and they pop up on both sides of my tree so was surprised to learn how uncommon the name was both generally and in Yorkshire. It’s a locational name based on an apparently “lost” village named “beo-croft” meaning bee farm. Tracing potential locations in the region could help me bring together the two sides of my family.

- Down to those names with fewer than 5,000 children born. Teal has my favourite origin story, as it is thought to be a nickname, meaning like a water-bird. One of my distant ancestors must have been graceful in their deportment. The Teal variant of the name is also strongly associated with Yorkshire with over half those born being from Yorkshire.

- There were fewer Reynards born than Housemans. Reynard does not in fact mean fox-like, but rather a popular medieval story book fox character was given this name and it stuck. It’s a surname with a number of variants, but 64% of the people born carrying the surname in this form were from Yorkshire meaning I stand a good chance of bringing them together in one tree.

- And finally, my favourite 3xG Grandmother, Hannah Demaine, keeps on giving. Surprisingly, given it means someone from the ancient French province of Maine, it’s a surname even more rare than Wellock and just as heavily concentrated in Yorkshire. The variant Demain, which I have also seen, only adds a few hundred births. This family of agricultural labourers are about as far from a Norman knight as it is possible to be and has whetted my appetite to research further.

There are a few more ancient names I should mention as being gateway surnames that have enabled me to reach back much further than I would otherwise have done: Wigglesworth, Hebden and Swale are all locational from Yorkshire. Pettyt leads me to a cousin, William, appointed Keeper of the Records in the Tower of London in 1689, who invented a wonderful family history claiming descent from King Arthur and might provide a connection to my oldest friend, Andrea (nee Petty). Finally, there’s Inglesant is a rare example of a surname derived from a woman demonstrating the strength of my female ancestry right back into the medieval ages.

And so it is that my beginnings reflect the end. It’s an (almost) Yorkshire story.

With much gratitude to Natalie Pithers for her two prompts, beginnings & surnames, which led to this blog and to all my ancient ancestors for picking such wonderful surnames.