More than once I have misjudged our ancestors. “Rogue” Robert Walker is perhaps the most blatant, but when I re-read my early attempts to capture George Brooks’ story, I realised I was in danger of misjudging him too. It reminded me that George’s declining career and the hoicking of his family from the fresh air of rural Bewerley into the slums of Bingley was due to poverty and circumstances beyond his control, not laziness and certainly not from choice.

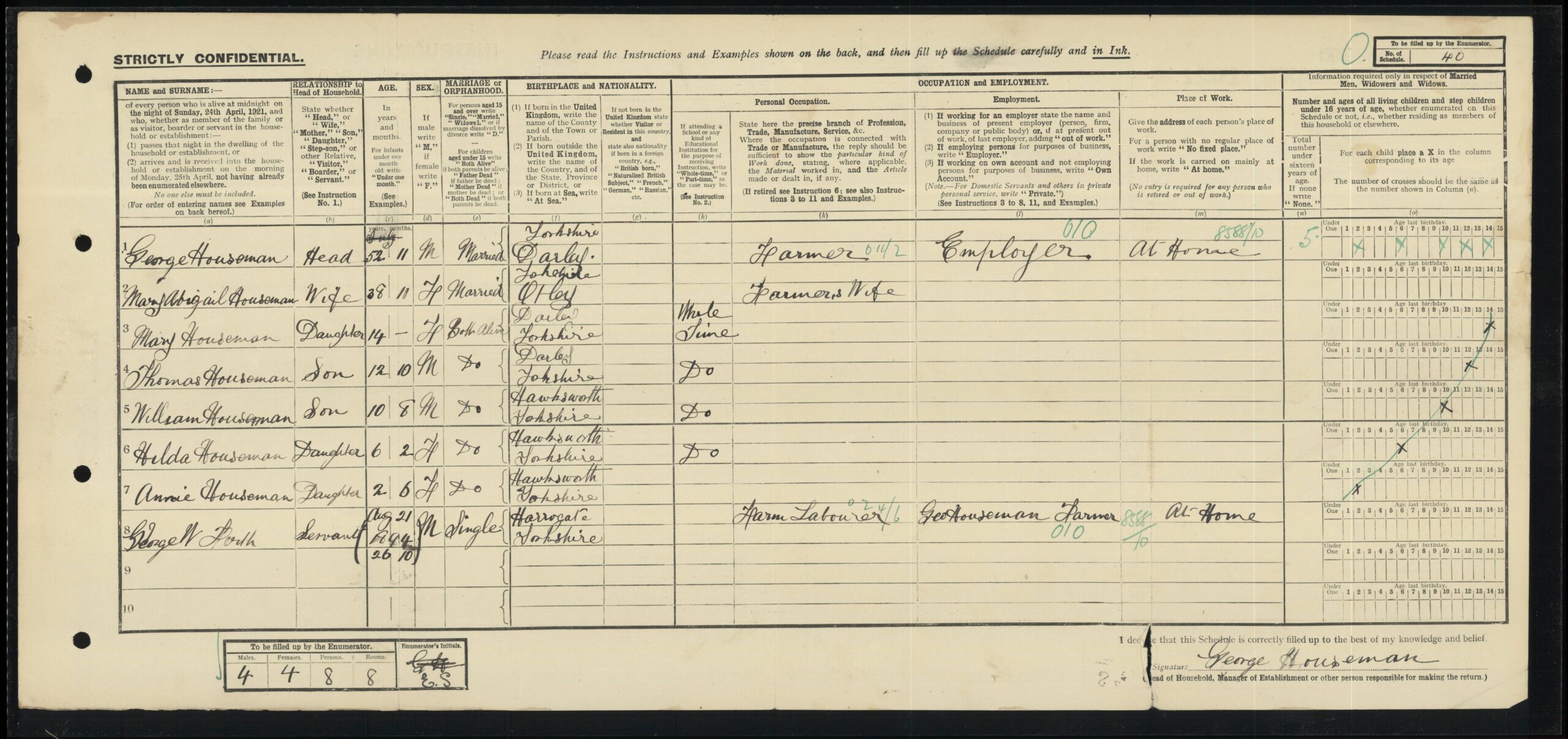

I do not know who to credit with sharing the above document, but I am grateful that they did. It shows George’s son, William, entering what I believe to be the Manchester Unity of Oddfellows in 1881. William was seeking to join a fraternal order set up to protect and care for its members. This must surely be a hardworking family, taking proactive steps to care for themselves and others. William is not George of course, but in 1881 he was still living with his father. Joining the Oddfellows must have been done with his consent and perhaps blessing.

This then is the rewritten story of Mary Holmes and George Brooks, our 3xgreat grandparents, through Grandpy’s father’s mother, Jane Brooks.

George was born on 8 March 1829 in Bewerley. His father, William Brooks, was already 43 when his last child was born and died when George was just fourteen. His mother, Anne Grange, was ten years younger than her husband, but she too, died, before George had ended his teenage years. George had an older sister, Ann, by this time married with her own family. His eldest brother, Harker, had died as an infant which left just one brother, also Harker, and ten years George’s senior. Harker promptly chose to emigrate to Australia with his young family and George was left alone.

(As an aside, Harker was a useful name to help track back this family – it helped confirm both George’s grandfather, Harker Brooks, and his great grandmother, Mary Harker).

George was not to be on his own for long. On 25 July 1850, George, having just come of age, married Mary Holmes, a local woman, a year his senior.

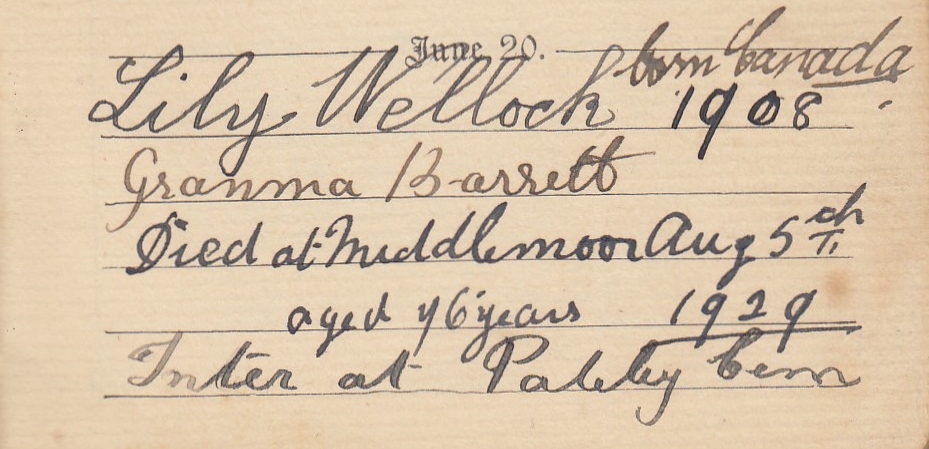

Mary was born in Bewerley on 24 February 1828, the fourth of six children of Jane Wilkes and Christopher Holmes. Like Harker, she too had had a deceased elder sibling after whom she was named. Fortunately, two elder siblings, Joseph & Ellen, and a younger brother, John, were all to survive childhood, with the youngest, William, dying in infancy. Jane & Christopher, too, appeared healthy with Christopher still recording his occupation as a stonemason well into his seventies. Unlike George, Mary was surrounded by family.

Importantly for my interpretation of this family, Mary & her siblings births had been registered at the Salem Independent Congregational Chapel in Pateley Bridge. There is a strong thread of non-conformist worship across our family, and I tend to associate this with a certain level of industry and temperance. It feels much more of an active choice. I wonder, though, why George’s sister Ann, had also been baptised in the Salem Chapel, but neither George nor his brothers were. Perhaps this form of worship had not been to the Brooks taste.

Mary & George settled into their new home in Bewerley. George, like his father-in-law, worked as a stonemason, Mary reared their children. I think Mary had the harder task. Jane (my great, great grandmother) was the first to arrive on 30 March 1851, a honeymoon baby. Eight more children arrived, one girl, Ann, followed by seven boys, regular as clockwork, every two years. They were a healthy bunch too. Only one, John Holmes, died in childhood (aged five).

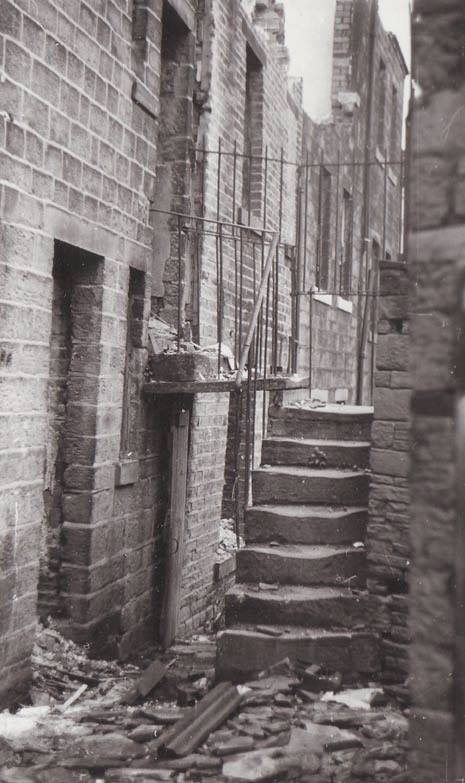

Then at some point between the 2 April 1871 (the census) and 20 Jun 1872 (John Holmes’s death) something happened to cause the family to move to North Street, Bingley. My best guess is that this was down to opportunities for work.

George was a stonemason. Whilst pre 17th century this was considered to be a skilled profession it had broadened somewhat by the 1800s to include quarrying and basic building and construction. The evidence in George’s life suggests to me he was more likely to fall into the latter category. Quarrying for stone & lime was an important industry in Bewerley, but the area had been in slow decline over the period from 1850 to 1890 as the lead mines closed leading to pressure on other occupations. With several growing children who also needed to find work, Bingley, with its factories, may have seemed an attractive option.

It proved the be a poor choice. The aforementioned John Holmes died shortly after the move. Then Mary herself succumbed to tuberculosis on 15 February 1876, a disease far more prevalent in towns. It also marked the start of the decline in George’s own career, from stonemason to mason’s labourer (1879 marriage) to unemployed stonemason (1901 census). The latter stage was entirely predictable, for who would employ a 72-year-old to undertake work that required physical strength?

With Mary dead, and the girls gone (Jane had long since left home to work as a live-in domestic and Ann had married in 1877) George was left with a houseful of boys. By 1879 Harker, too, had possibly left home, but that still left William, George, Joseph, Christopher and Thomas. Just like so many widowers in my family, George had a solution. On 3 August 1879 he remarried, to a spinster named Ellen Emmott, a 42-year-old domestic servant. Too old in 1879 to have children of her own, Ellen would have been a wonderful asset for a household consisting only of males.

As regular readers know, one of the aims of my research is to ensure that women’s lives are recorded and with no children of her own, Ellen is at risk of being forgotten. So indulge me whilst I take a short diversion into Ellen’s own story.

Ellen was the illegitimate daughter of Isabella Mitton born on 17 January 1837 in Addingham. It wasn’t until 28 October 1839 that Isabella married John Emmott, so he clearly wasn’t the father, and the documentation seems to suggest he never treated her as his own. John was a blacksmith, prosperous enough to leave a, still legible, York stone memorial in Addingham churchyard. His gravestone also records the death of Isabella and of their first child, Alice, born in 1841. By 1851 Ellen had left mother’s growing family and went to work as a domestic servant. At the age of 42, she married George and essentially acted as his (unpaid) housekeeper and they descended together into slums until George’s death in 1901. It seems that none of the Brooks’ brothers thought to invite her into their own homes when their father died, but she did find peace. She was taken in by her two unmarried half sisters, Ann & Phoebe (eleven and seventeen years younger than her), who were housekeepers at a boarding house at Arnside, Morcombe Bay. Phoebe, the second of the two sisters to die, left an estate of £2,400 in 1930, so the sisters were in a good place to support her Ellen until her death in 1913. I am happy to think that she lived out her last days in peace with her sisters.

Of course, Ellen’s story has essentially given away the end of our tale. George junior died aged twenty-one in 1880 and then one by one the Brooks’ brothers left home. Thomas, the youngest, was last to leave. By 1901 George & Ellen lived alone, having moved to Foster Street in Crossflats, until on 4 September, at the age of 72, George died. He was reunited in burial with Mary and his sons, John Holmes & George in Bingley cemetery.

With much gratitude to a man named Adrian Rhodes, a descendent of Mary & George through their son, William Brooks, for sharing various documents about William on ancestry including the one which I shared at the start of this blog. Thanks to Nigel Brooks for his dedicated work on the Brooks family line which makes cross checking my work so much easier. My thanks too, go to Mary Holmes & George Brooks for reminding me to take equal care of all my ancestors.