We’ve been sharing snowy pictures on the family whatsapp this week – one of my sister’s even shared a picture of some drifts which had formed at Greenhow Hill – a sign that some element of these stories is being absorbed. There was a bit of grumbling about school closures and disrupted travel plans but mostly it was delight in the white wonderland outside the window.

We, however, have solid, insulated, centrally heated homes, warm clothes and, even if tomatoes are scare, a functioning food system. Our 18th century ancestors had none of these things. The poorest amongst them were living in shabbily built huts where the cold wind whistled through both open spaces for light and gaps in the walls, roofs and doors. Clothing was limited and threadbare, food dependent on what a daily wage would provide. Winters, a daily struggle to survive.

It might well have been snowing when Sarah (Dickinson) & John Windsor married at St Oswald’s in Arncliffe on 15 January 1771 but there would have been comfort in hearing the old bell, already 400 years old, pealing out loud and clear down Skirfare valley. In their first few years of married life Sarah & John made regular, happy, trips to the church to see their children christened. Mary (our 4x great grandmother) was the first to arrive, baptised on 23 February 1773. She was followed by Jane (ch. 24 July 1774), Issabella (ch. 7 July 1776), John (ch. 9 November 1777) and Sarah (ch. 7 May 1780). Sadly Sarah survived only a few weeks and was buried on 10 June 1780. Still four children out of five surviving infancy was pretty good odds in the late eighteen century.

In the church baptism records John is listed as John Junior, recognising another, older, John Windsor who was also producing children at this time. However, it also tells us that John Junior did not have another distinguishing factor such as a trade or a farm tenancy. The family’s ability to survive would have depended on both John & Sarah working every day that work was available.

When baby William was baptised on 6 July 1783, news of the violent eruption of the Laki volcano in Iceland may not even have reached Arncliffe. Arncliffe was a bit of a backwater – it was still using the Gregorian calendar to record baptisms and burials thirty years after we officially adopted the Julian one. The sulphur dioxide gas smothered Europe, blocking ports and increasing deaths amongst outdoor workers. It was disastrous for Iceland, some 20 – 25% of the population were to die as a result of both the immediate explosions and the following famine. But in Arncliffe, far from the sea and protected by hills? The understanding of a volcanic winter is a new one.

Temperatures dropped by an average of 1OC and the winter of 1783 – 1784 was especially severe. In the UK alone it is estimated to have caused an additional 8,000 deaths. Based on Sarah & John’s experience, and that of the parish of Arncliffe as a whole, it seems this number could be significantly understated.

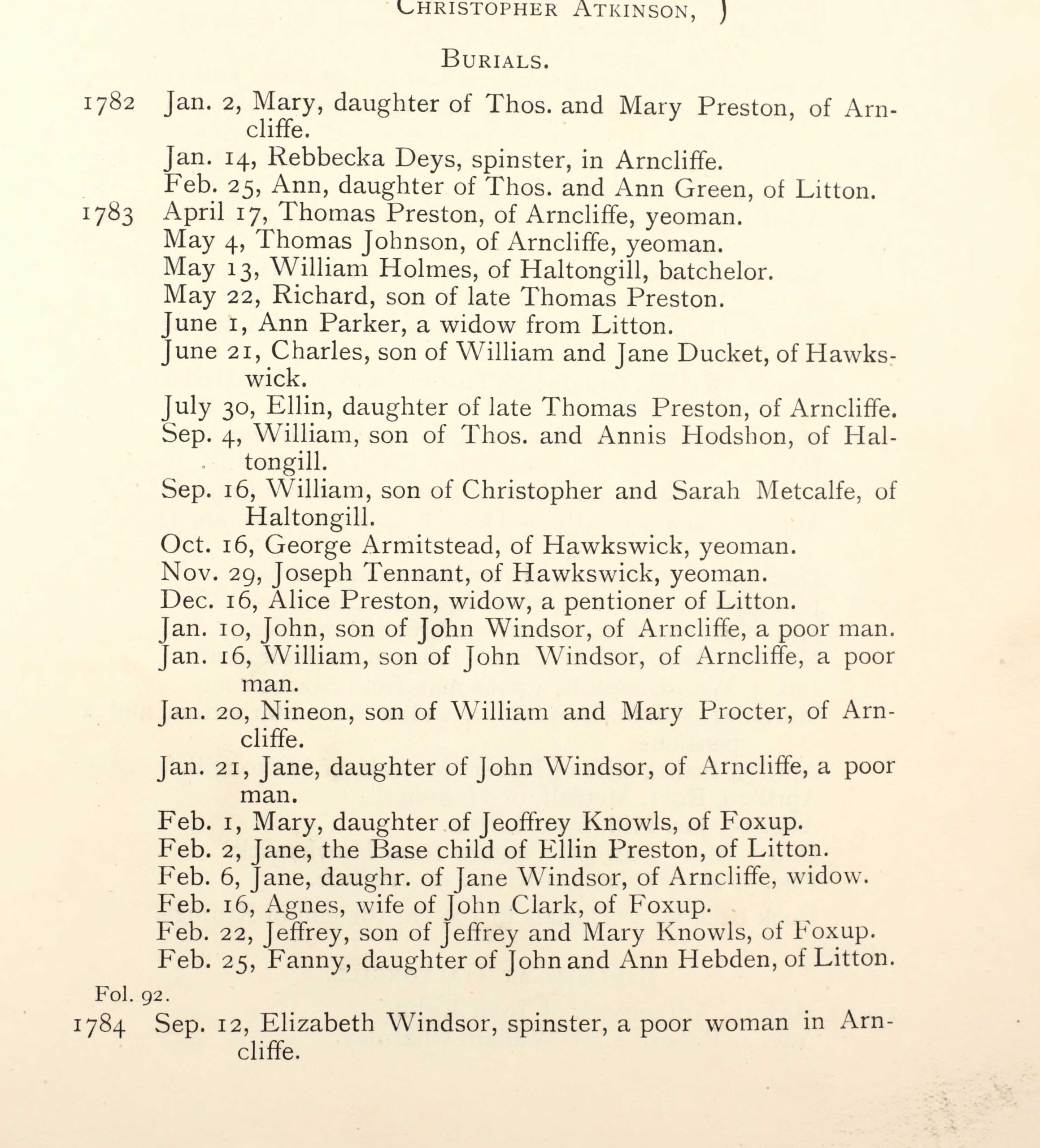

Burials in Arncliffe for the year 1783 (meaning 25 March 1783 to 24 March 1784) were approximately double those in the preceding five years. Amongst them were John (bu. 10 January 1783/4, aged six), William (bu. 16 January 1783/4, not yet one) and Jane (bu. 21 January 1783/4, aged eight), all children of John Windsor, now described as “a poor man.”

When families faced starvation in the eighteenth century, food for was prioritised for the workers to ensure they could keep earning. John, as the adult male, would have been first, Sarah, as an adult female, second. Mary, the eldest child, would have been eleven and she too, would have been contributing financially, and, presumably, fed. Assuming all three were out looking for any available work that would have left eight year old Sarah in charge of three shivering, starving children. Records don’t show whether it was starvation or sickness which killed the three children in just two weeks, but I am sure it was Laki.

After that long, cold winter life improved for the Windsors, at least as far as the next generation were concerned. Sarah & John had three more children: James (ch. 13 November 1784). Barnabas (ch. 23 July 1786) and finally Betty (ch. 21 October 1792) who was likely younger than her niece Jenny, Mary’s oldest child. Whilst I haven’t yet been able to trace what happened to Isabella & Betty, James & Barnabas both moved to Leeds, learnt trades, had families and lived long lives. Mary married Richard (2) Wellock and became part of my Wellock story. Together they re-established the Wellock family link to High Garnshaw and went on to have around fifty grandchildren including our own great great grandfather Richard Wellock. I am the legacy of the hard choices which Sarah & John faced during that bleak winter of 1783 and I am grateful for them.