2 January 2009 (Monday)

“It’s been really, really snowy today. Setting off from Leeds was fine, bus & train running to time. London was a different matter. I arrived at work about a quarter to eleven – I was the only senior finance team member in! Times like this don’t happen very often in our lives and its worth just sitting back & enjoying the snow (& the now).”

In 2009 I was commuting from Yorkshire to London each week and totally bemused that London seemed to have ground to a halt that week. In Yorkshire hill farming territory, stormy weather means snow. Here is the story of three memorable Yorkshire winters illustrated beautifully in three of my grandparents’ own words.

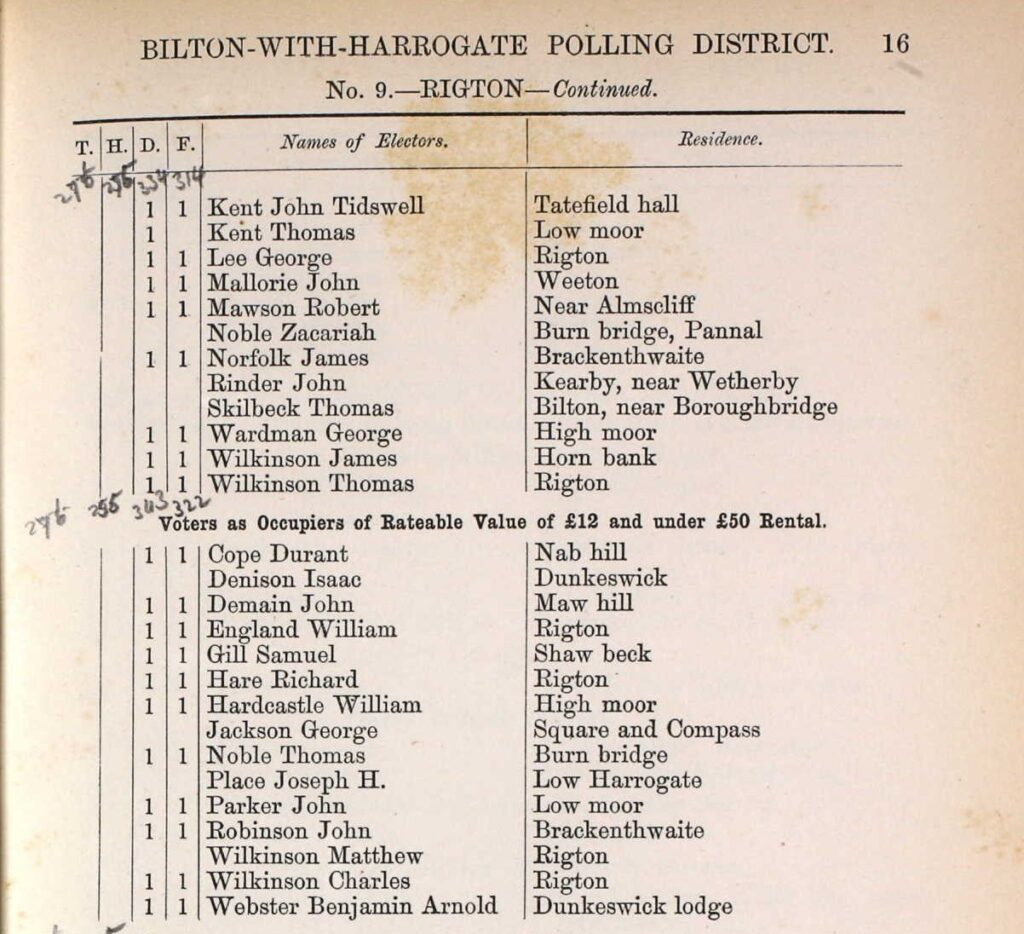

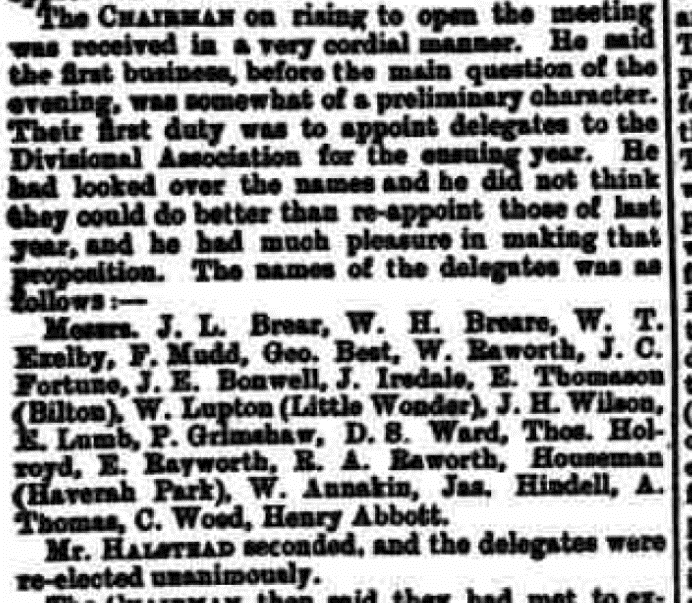

The extracts in this blog are taken from: letters sent between Mary Booth (Nana) & Walker Barrett (Grandpy) in 1947, Mary Houseman (Grandma)’s memoir “The Changing Years” and my transcript of an oral history interview with Walker Barrett, recorded c. 2011 as part of the Washburn Heritage Centre’s archive.

1933 – “up in’t telegraph wires”

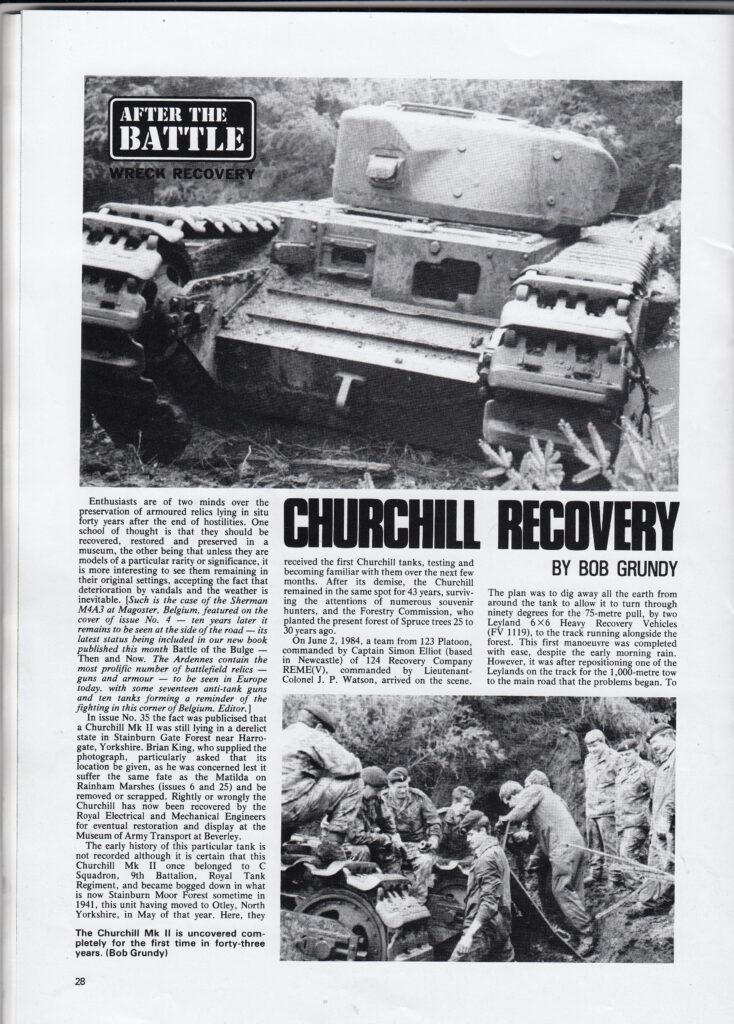

25 & 26 February 1933 saw one of the worst blizzards to ever hit the British Isles. It snowed continuously for 48 hours and there were fourteen foot drifts on Yorkshire’s moors and dales. In 1933, Walker Barrett was living in Greenhow Hill, a particularly exposed Yorkshire village.

“A lot of snow, 1933, snow were up in’t telegraph wires…..All that snow come right over the house top. Our cattle…. there weren’t water bowls in them days, they went out to the water trough. There was a snow tunnel…..trough well designed, cos it was turned off in’t house ….went underground and came up underneath t’trough, you see. Well designed cos they didn’t freeze up.”

Mary Houseman tells a similar story.

“I’m sure that winters were more severe then. Many times the roads were blocked solid for thirty days and we could not get out anywhere. We had to dig a path to get across the yard and often all the windows, taps and water would be frozen up. I once remember having to carry it all in buckets from the tank in the stock garth twice a day to water all the cows. When we started making milk we took it in cans to Norwood Edge with the horse and a homemade sledge. Some of it just stood there for days, the milk wagon couldn’t even get there. We carried hay on our back to feed the sheep. I have never worn trousers and my skirt got wet through trailing on top of snow drifts”

1947 – “It took us all day digging through high drifts just to get across the yard into the buildings”

Mary Houseman was still living at Prospect Farm, Lindley

“The winter of 1947 will be remembered a long time or should I say early Spring. At the end of February came the worst snow in living memory. Day after day it continued. Each morning when we wanted to get out of the back door we had to dig it. It took us all day digging through high drifts just to get across the yard into the buildings. We were able to milk but nothing to put it in so it was just put down the drain….It was almost impossible to get to the sheep. We hadn’t a tellyphone [sp] so we were cut off from everything and everybody for a long time but we had plenty to eat and coal to burn. When the storm did stop three of our men and some of Baxter’s used to go and dig the lane out by hand as no tractors then. The snow was frozen so hard that we walked on top of it right across to Stainburn one Sunday. We could not see any walls just the treetops stuck out. The sun shone through the day and it froze hard at night like the countries where they ski. When it did start to thaw it was waist deep in slush. When the roads did eventually get a way through they were still a foot deep in ice and bad to travel on. The poor sheep were in a sorry state. Some lost their sight it was called snow blindness. We did eventually get them near home by walking in a line on the hard path where Dad went everyday to take hay. Some could not stand so they had to be carried in a sack. We gave them milk to drink to give them a bit of nourishment and slowly they got a bit stronger. I don’t remember loosing any but a lot of sheep on the moors were snown under the drifts and never found until the snow had gone. Food for cattle and people was dropped from the air for some farmers in isolated areas…..The road over the moor was impassable for weeks. Gangs of men with shovels and spades came to cut through the drifts. I hope we never have a snow like that again”.

Walker Barrett, now at Stainburn, continues.

“We lost a lot of sheep, we did that year. But 47 snow. There were just eight weeks tilt milk wagon coming into the yard. It came in on’t Sunday when it started snowing that Sunday morning and it was just eight weeks on’t Monday before the milk wagon came into the yard

We used to sledge it down’t fields with horse & sledge and come out down at bottom of Leathley bank

He [Henry Barrett, Walker’s brother] was at Lindley….Although when we were blocked in at Stainburn he could go out every day. Cos he used to bring van and pick our milk up off road and take it down to his place to pick up”

What Walker didn’t talk about in his interview is the impact it had on his & Mary Booth’s courtship. Their letters give a sense of how long the snow kept the two young lovers apart.

From Mary to Walker, postmarked 5 February 1947 “You did right not to come last night dear as the roads are bad around here…..I was watching the weather most of the afternoon then I finally decided that it was not fit for you to come about teatime….do come up any night dear when it is fit but please don’t risk it when the roads are bad.”

From Walker to Mary, written 5 February 1947 “Well dear I am trying to write you a few lines but when’t will be posted I don’t know, we have had no post since Monday & the post doesn’t look like reaching here this week. Did you expect me on Sunday, I was sore disappointed, but it really was not safe to come, I could have got to Askwith but not back to Stainburn then I would have had to sleep with you dear. The roads around here are bad don’t think the Wolseley will be out this week. We shall have to cut the lane right from the yard bottom nearly to Ridleys & then it is blocked from the lane ends nearly to Housemans but there are 12 Germans started at the bottom end”.

From Mary to Walker, postmarked 9 February 1947 “The post man had to walk part of the way from Otley as it had drifted it again. When I saw him coming here I didn’t dare hope for one from you. As I’d been longing to hear from you all the week….. You sound to be well blocked in down at Stainburn. We’d heard from one or two folk how bad it was. It’s not much good digging as the wind fills it up again with more snow. We managed to get down to Otley on Friday but from Askwith to Otley there’s only way for single traffic so we just trust to luck that we don’t meet anything coming the other way….. But please dear don’t start to bike up as it’s too far in this weather and the roads are very rough.”

From Walker to Mary, likely February 1947, “We are pretty well cut off only open to the Bank top yet & it’s blowing it in again & snowing like blazes. I’m well & truly fed up, but I’ll pop in one of these nights. I intended coming tonight. I think we have got above our fair share of this snow up here many places the drifts are 6 & 14 ft. the Bank was full. I go through the back of Clifford & down the Bank with the milk…… our car will be lucky if it’s out for next weekend. I have never seen it since last Saturday night. I’ll have to dig it out & warm it up tomorrow & see what a car looks like”.

From Walker to Mary, 16 March 1947 “I am not so bad but fed up with the weather. Tt looks as if it will be Tuesday or possibly Wed before we manage to get the car out. Only Bernard cutting from here…..”

1979 – “special day”

For Mary Houseman the winter of 1979 was far more memorable for the birth of a granddaughter than for the strikes which were causing such difficulties for the rest of the country.

1979 started with snow and ice through most of January and February we put electric fires in the parlour to keep it from freezing up and some days the milkman could not get up for the milk and January 23rd was another special day in our family. Ann got another baby girl, after a few anxious days wondering if we would all be snown in. It was a third daughter, but they chose Anna Marie for her name, a bit more up to date than just Mary. They were both well and soon back home to the ice and snow.

ADD: I recently came across this wonderful short video on BBC Rewind, Snowcats Rescue Sheep – perfectly illustrating the snows of Yorkshire in 1979.

So next time there’s a sudden snowstorm that causes mild inconvenience, sit back & enjoy the snow (& the now).

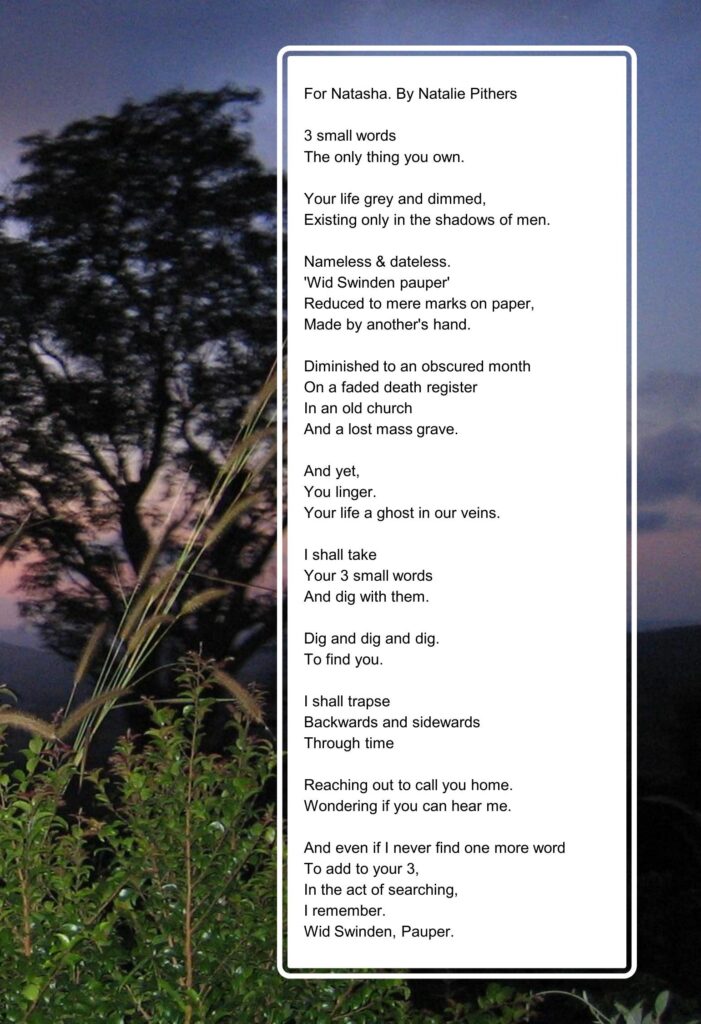

With love and thanks to my maternal grandparents Mary Booth & Walker Barrett for saving their letters of thwarted visits and to Walker Barrett & Mary Houseman for sharing their memoires in oral & written form.