What lovelier question could there be to ask a family historian on her birthday weekend than “What churchyard do you want to visit today?” “Kirkby Hill” I responded promptly, as I’d long wanted to go and find the gravestone of my great, great Uncle Walter, who was killed by a shotgun at the age of seven. “Along the way we could call in and see the Roman mosaics at Aldborough?”. We found the gravestone in question, bumped into my Aunty Sue in the Oxfam in Boroughbridge (which led to a whole new set of discoveries), visited the mosaics and found ourselves unexpectedly enjoying tea and cakes on the village green of Aldborough. I left Mum and Joe chatting with strangers on the next door table and wondered off to mooch around the old church. A perfect day.

Aldborough (“old town”) feels like somewhere time stopped. Trade had long since moved to its upstart neighbour, Boroughbridge (when the Roman’s built a bridge there). By the 1700s, it had become a rotten borough, controlled by the local landowner, with parliamentary seats available for a price, more lucrative than investing in the village itself. St Andrew’s Church, though, remained the centre of a significant parish, including Boroughbridge, as late as 1866. The church was rebuilt around 1330 after being destroyed by Scottish raiders, with a chancel and tower built in the fifteenth century. The stained-glass windows were a much later addition, but it looks, and feels, largely as it would have at the end of the eighteenth century.

Largely as it did, I discovered later that week, when my 5xG Grandparents, Frances (Morell) and Thomas Robinson were married there on 25 August 1796, two hundred and twenty-seven years and four days before I walked through the same heavy oak doors.

Thomas was an agricultural labourer and although this is a potentially iterant profession, the family appear to have settled in Boroughbridge where children arrived at regular intervals to be baptised at St Andrew’s: George (11 June 1797), Thomas (27 October 1799), Mary (my ancestor) (17 December 1802), Sarah (10 February 1805) and finally William (21 March 1812).

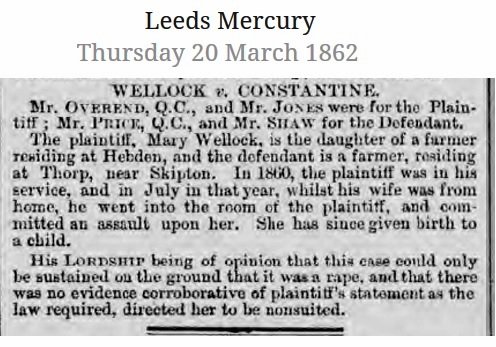

Unlike with many other of my lines, this was not to be the start of a generational connection to Boroughbridge, for the children scattered. George moved to Marton cum Grafton where he followed in his father’s footsteps taking up agricultural labouring work, Thomas moved to Colne, Lancashire, although returned to marry Mary Dickinson in 1821 and, potentially, became a soot merchant. Mary moved to Leeds and then, following her marriage to John Howson, to North Rigton. Sarah did marry a local man, George Johnson, in 1829, but he appears to have died before they had any children, as she too, moved to Leeds where she married John Kerton in 1838. Of William there is, as yet, no sign.

St Andrew’s holds a potential clue, a Georgian bread shelf, indicating the necessity of charity for the parish poor. Work, at least work which paid sufficiently well to support a family, was likely in short supply. The growing towns and cities of the industrial north provided a solution.

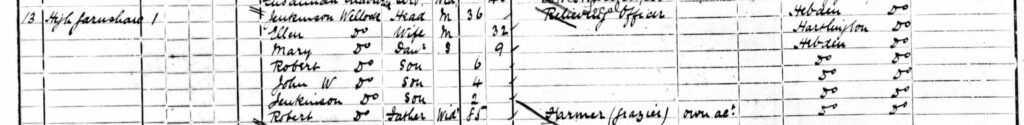

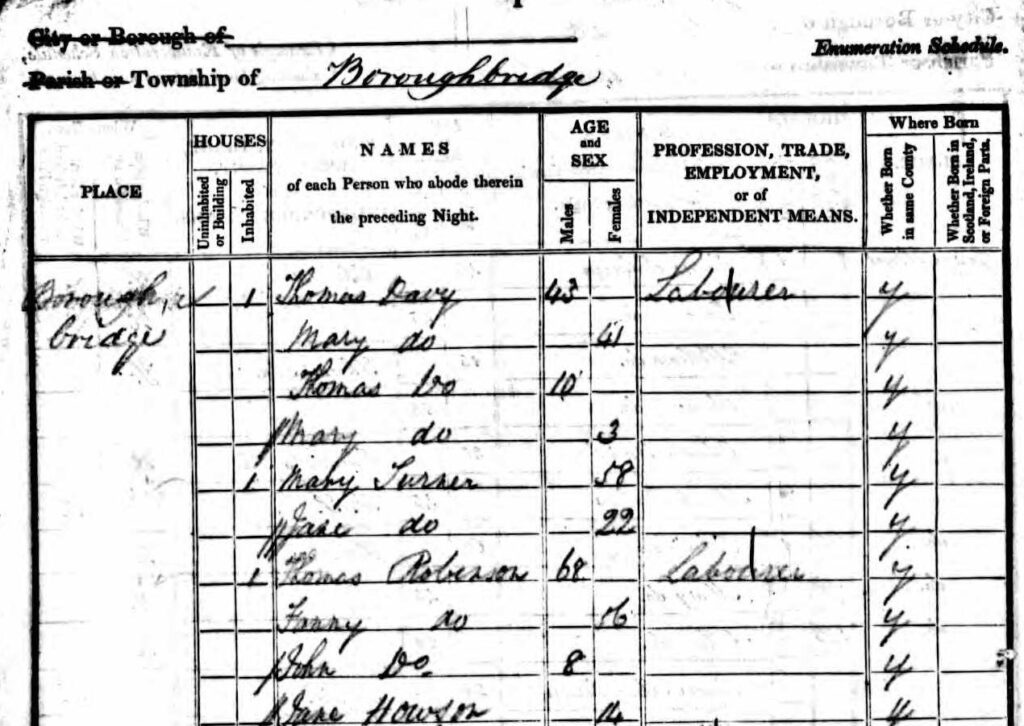

I’ve often wondered how, or even whether, illiterate families from the nineteenth century stayed in touch once children moved. This was too early for the train, so travel would have been expensive and time consuming, and if the parents couldn’t read, and the child couldn’t write, what was the point of a letter? In this case, it seems they must have done, for in the 1841 census, Thomas (68) and “Fanny” (56) had visitors, John Robinson (8) and Jane Howson (14), two grandchildren sent to live with and support their elderly grandparents. I am grateful they were not alone, and even more grateful that it was my 3xG Grandmother, Jane, who was there because it was her presence, together with the birthplace of her mother, Mary, which had led me to identify Frances and Thomas in the first place.

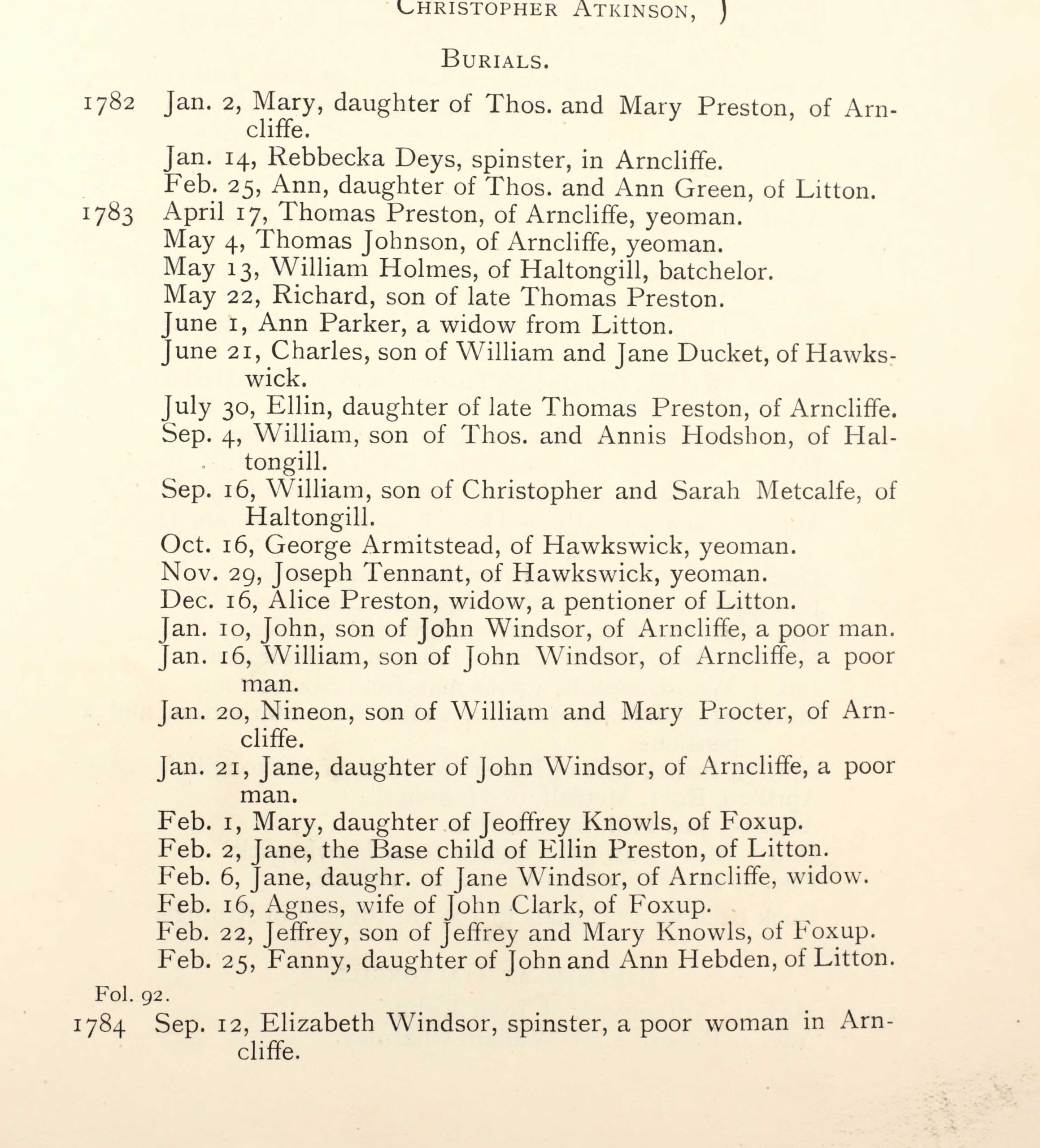

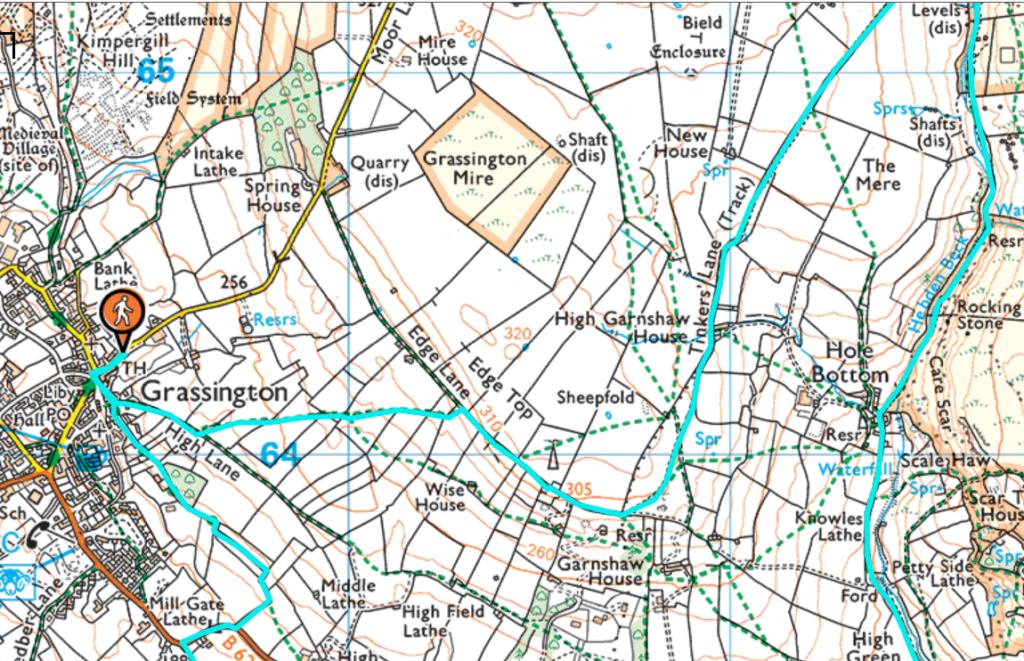

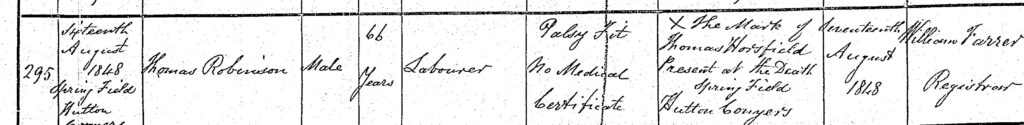

Not that grandchildren took away the need to work. By his seventies, Thomas would have been struggling to find employment, yet still he laboured. For on the 16 August 1848, he died, of a palsy fit, in Spring Field in Hutton Conyers. In his death certificate, an illiterate co-worker gave Thomas’s age as sixty-six. In his burial record, at Aldborough two days later, his more likely age of seventy-seven was listed. It was harvest time, when any physically able ag lab should be able to find work and yet Thomas was working nearly eight miles from home and, it appears, had felt it necessary to knock a decade off his age in order to secure the position.

Frances struggled on alone in Boroughbridge, which is where we find her in 1851, aged 76, her occupation listed simply as “poor” perhaps struggling to make the weekly service at St Andrew’s in order to claim some bread for the week. Eventually though, she must have moved in with her son George, for it was in his home in Marton cum Grafton where she died, aged 83, of nothing more specific than “old age” on 19 July 1854. I like to hope that she is buried back at St Andrew’s, with Thomas and where her records start, but her burial remains untraced.

Despite records surviving from the 1770s in Aldborough, there are no obvious baptisms. Morrell should have been a traceable family, especially as George also married a Mary Morrell, but I have found nothing that fits. Thomas was an agricultural labourer and, with only the 1841 census to go on, could have been born anywhere in Yorkshire. Illiterate, it is no surprise that the ages given in the various records are not entirely consistent. So, I’ve called it. They are not a brick wall but can be celebrated and written about as an end of the line, being as far back as I am expecting to trace. With much gratitude to my 5xG Grandparents, Frances Morell, Thomas Robinson and their granddaughter Jane Howson for being together on 6 June 1841 and to my Mum’s husband who suggested a spontaneous trip to Aldborough which supported the writing of this story.