This is part of a series of brief biographies of earlier ancestors.

On Monday, 1 March 1920, Martha would have been celebrating her 90th birthday. It had been a fair February that year so perhaps Martha sat on her front doorstep of Blaeberry Croft cosily wrapped in her woollen shawl and headscarf with her faithful dog by her side. How might she be reflecting on those past ninety years?

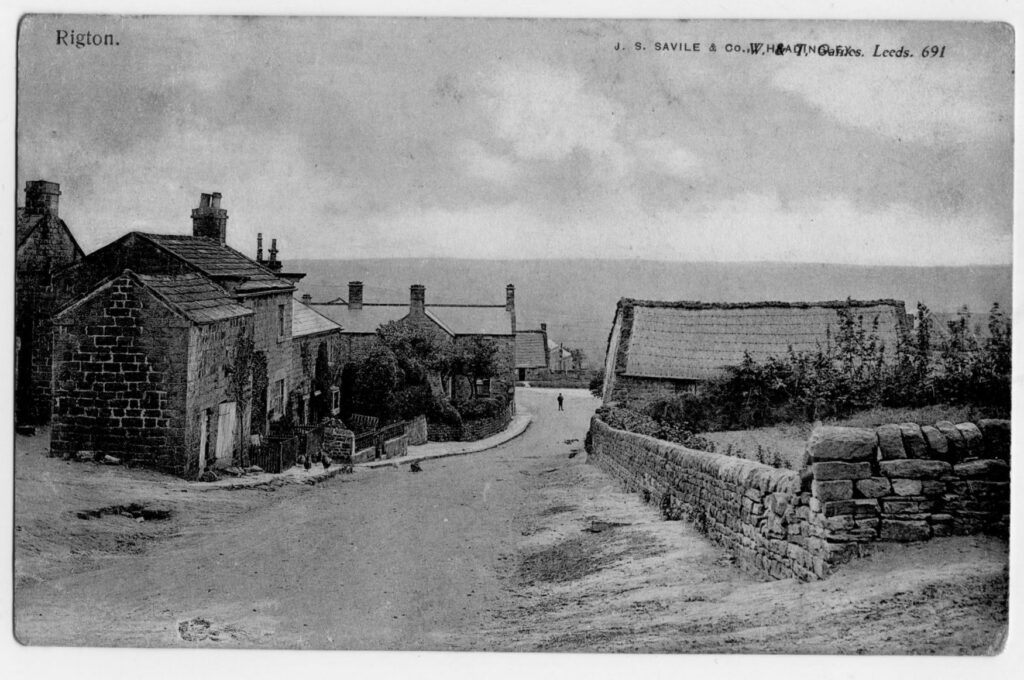

Martha had lived her whole life in North Rigton, a compact Yorkshire village situated towards the top of a hill. It’s a popular place these days, just a few miles to Harrogate, close to Weeton station giving easy access to Leeds and beyond, with an excellent primary school and a welcoming pub.

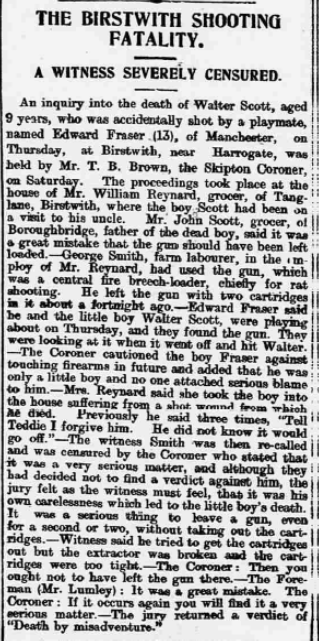

During Martha’s childhood it would have felt very different. Yes, the Square & Compass served ale of course, to the men of the village, but it also acted as the place where inquests and other village meetings were held. The church wasn’t built until 1911 . A methodist chapel had been built in 1816 but was replaced in 1932. Farming was hard and winters bleak. Harrogate and Leeds would have felt another country.

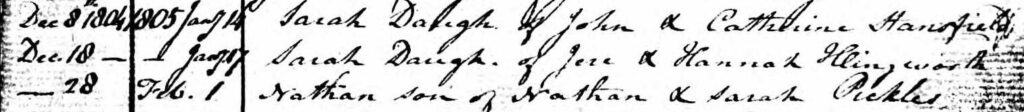

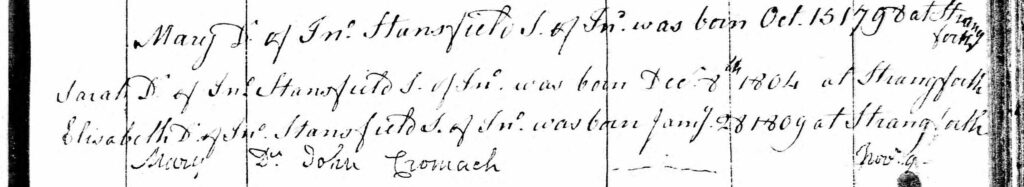

Martha was the youngest of five girls and, for a period of time, very much the baby of the family until joined by her illegitimate niece, Matilda. Her older sisters ranged in age from five to sixteen and when she was born in 1830 Martha’s parents, Sarah Halliday & John Handley, likely despaired at the arrival of yet another girl. John was a gamewatcher and farmed a few acres, a precarious existence which relied on sons for labour in their youth and the “pension” for parents in their old age.

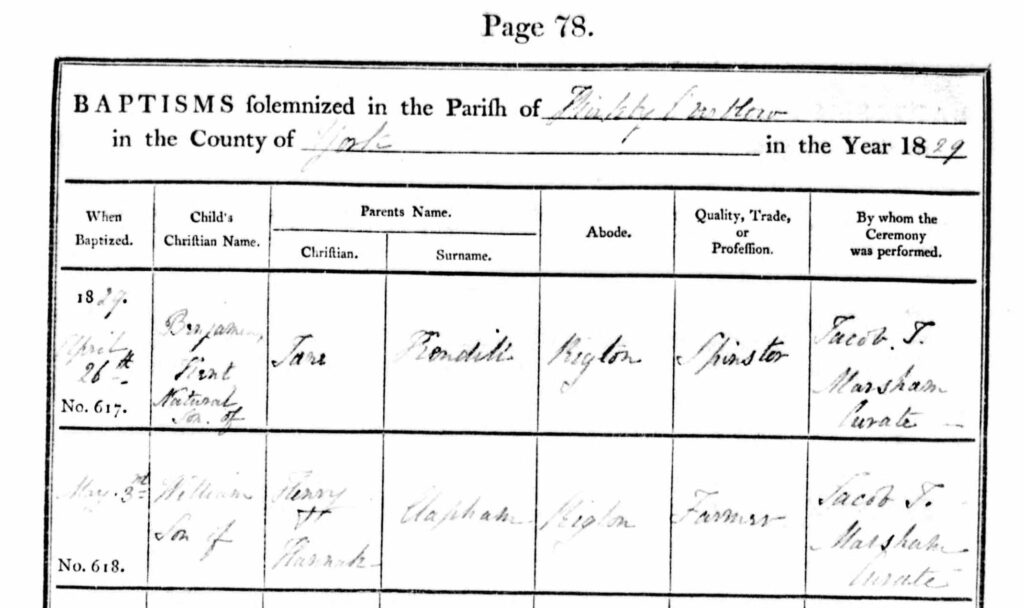

Then there was William. Likely also a baby of the family as his parents, Hannah Hardcastle and Henry Clapham were aged around 45 and 60 when he was born on 12 March 1829. The Claphams were tenant farmers also living in North Rigton where their family had lived for many generations.

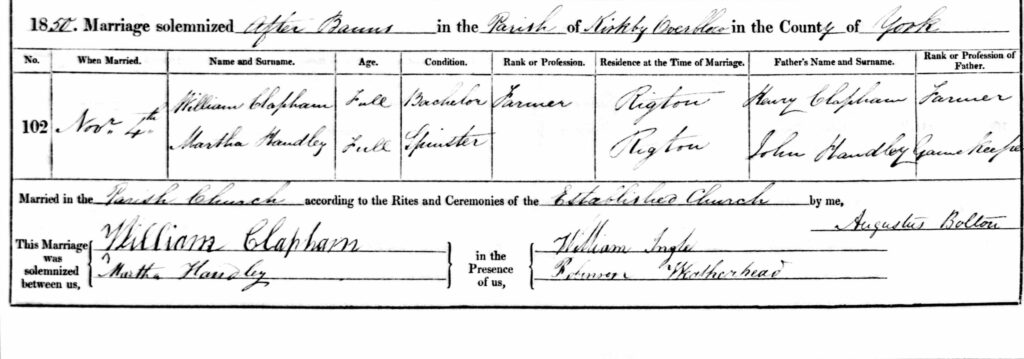

William & Martha were close neighbours, listed on adjoining pages in the 1841 census, and on 4 November 1850, with William having both become the head of household following the death of his father and attained the age of twenty-one, the pair were married at Kirkby Overblow church.

Martha’s reflections likely moved on to her married life and that of her family. Nine children arrived in quick succession all surviving to adulthood. Samuel, the eldest, born in 1854, married to a local woman, with four children all already married, ten grandchildren and more to come. Martha might even have had a letter in her hand from Samuel’s son, William, who had emigrated to Canada a few years ago. Joseph, her baby, born in 1871, had got married in Hartlepool, but had thankfully chosen to come back to nearby Fairview Farm, so Martha would have regularly seen his six children. Samuel & Joseph were doing just fine.

It was the middle children Martha worried about. Henry (b. 1856), Hannah (b. 1858), William (b. 1861), Abigail (b. 1866) and Mary Grace (b. 1870) had all remained unwed. Henry had died in 1902, but the others were all still living close by. They supported each other with the sisters acting as housekeepers for the brothers and Mary Grace still living at home with Martha, but was that a life? And of course Sarah (b. 1859) – did she marry, die or disappear after 1881? I haven’t been able to trace her, but Martha would have known.

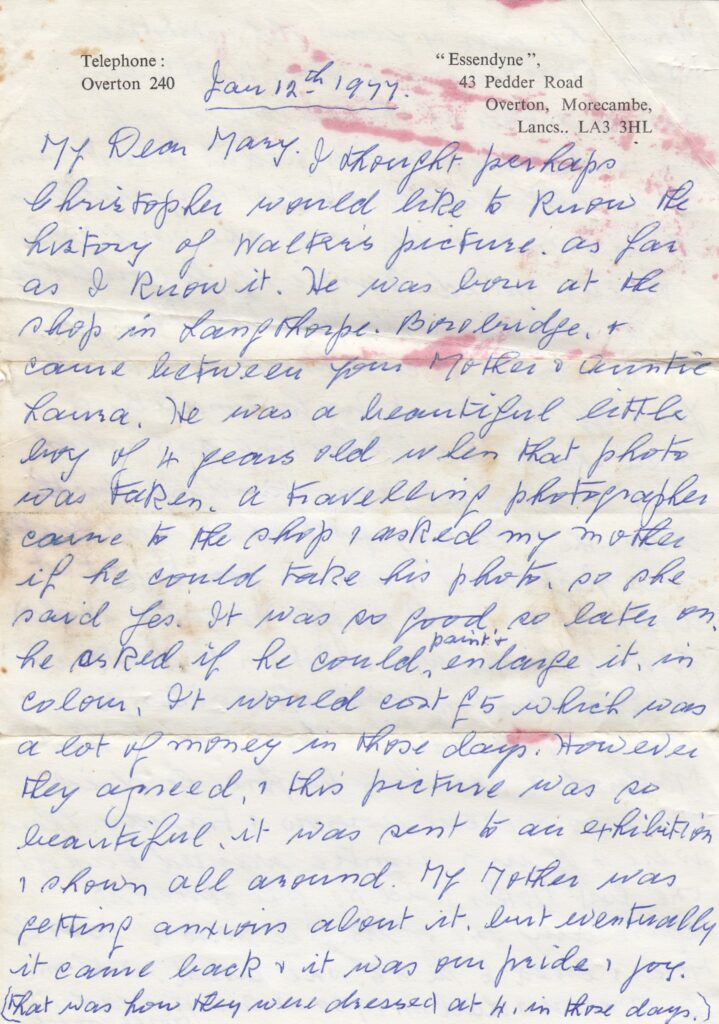

Then there was Martha or Marie as she now liked to call herself. Born in 1863, she’d always thought differently. “As a young country girl she used to tramp the 12 miles to attend the meetings of Charles Bradlaugh.” Marie was married to John Greevz Fisher and living in Leeds. Her five children, Auberon Herbert, Wordsworth Donisthorpe, Constance Naden, Spencer Darwin and Hypatia Ingersoll were named after anarchists and radical philosophers. Marie was a militant feminist and active suffragette and deserves her own story but right now, sat on her Rigton doorstep, Martha must have wondered how on earth she’d come to raise such a daughter.

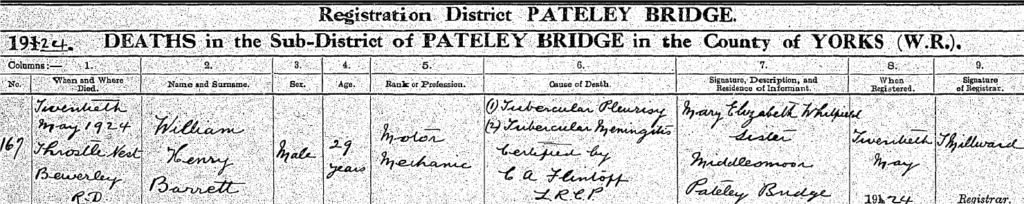

The time for sadness would come later, when, perhaps one of Martha’s children would take her on the short trip to Kirkby Overblow church. After more than forty years of marriage, William had died on 13 December 1893 and was buried where the couple married, in Kirkby Overblow together with their son, Henry. That would be the time for sadness and in the meantime, Martha could be happy with her ninety years, surrounded by her family in the village she was born. Martha was to die the following year on 29 March 1921 and was buried with her husband at Kirkby Overblow.

With much gratitude to Martha Handley & William Clapham, my great, great, great grandparents through my paternal Grandad, for bringing up such a wonderful family.

A brief addendum

Sarah didn’t, as it turns out, disappear. She married Richard Hallewell, moved to Armley and had two children, Mary Ellen & Richard Bertram. Indeed, Mary Ellen was staying with her grandparents at the time of the 1891 census which is a reminder to double check all the available evidence. Sarah was widowed sometime between 1909 and 1911 and ultimately moved back to the area.

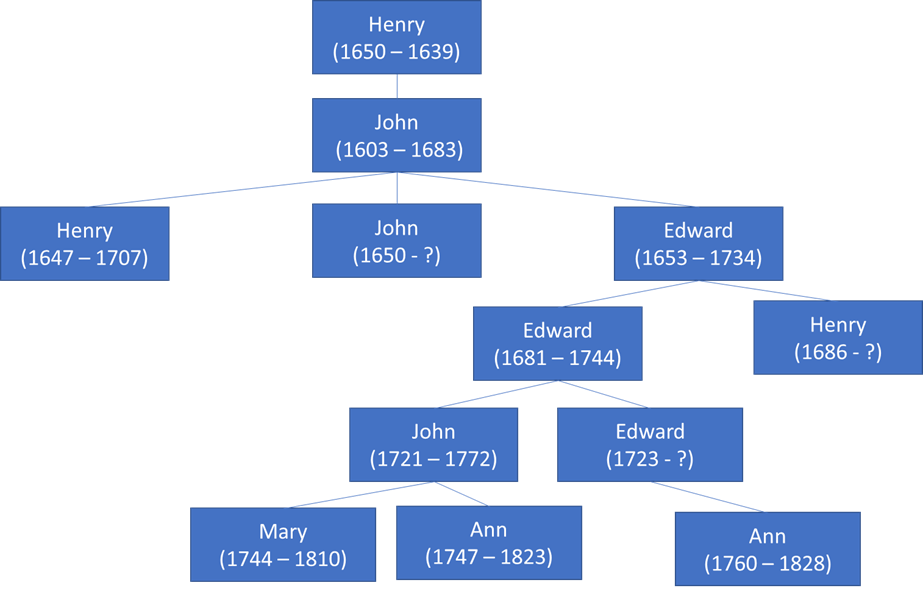

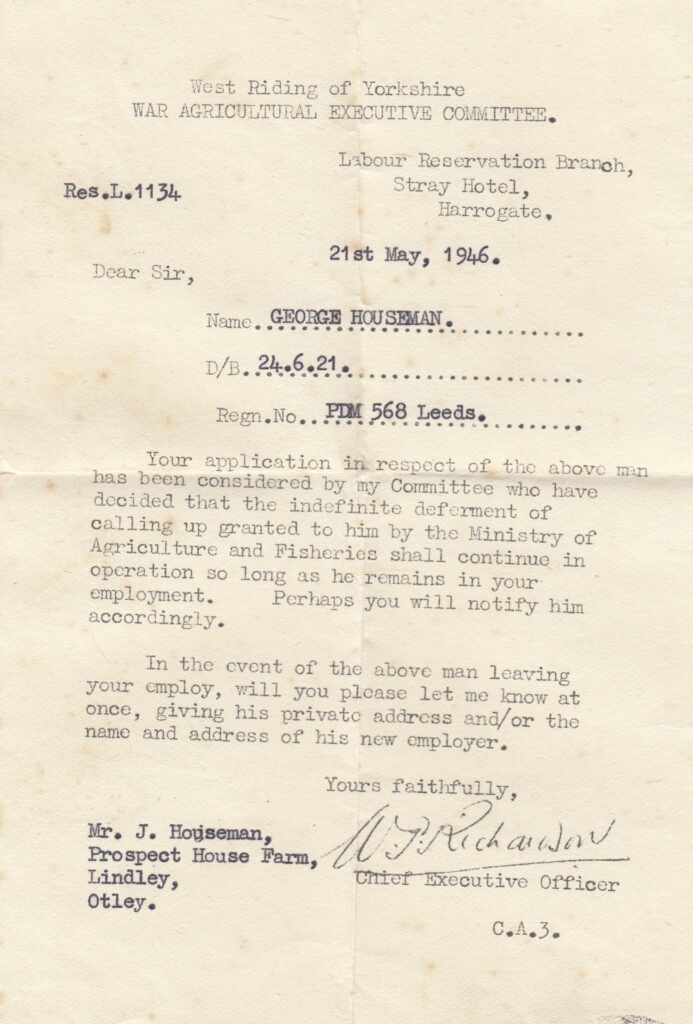

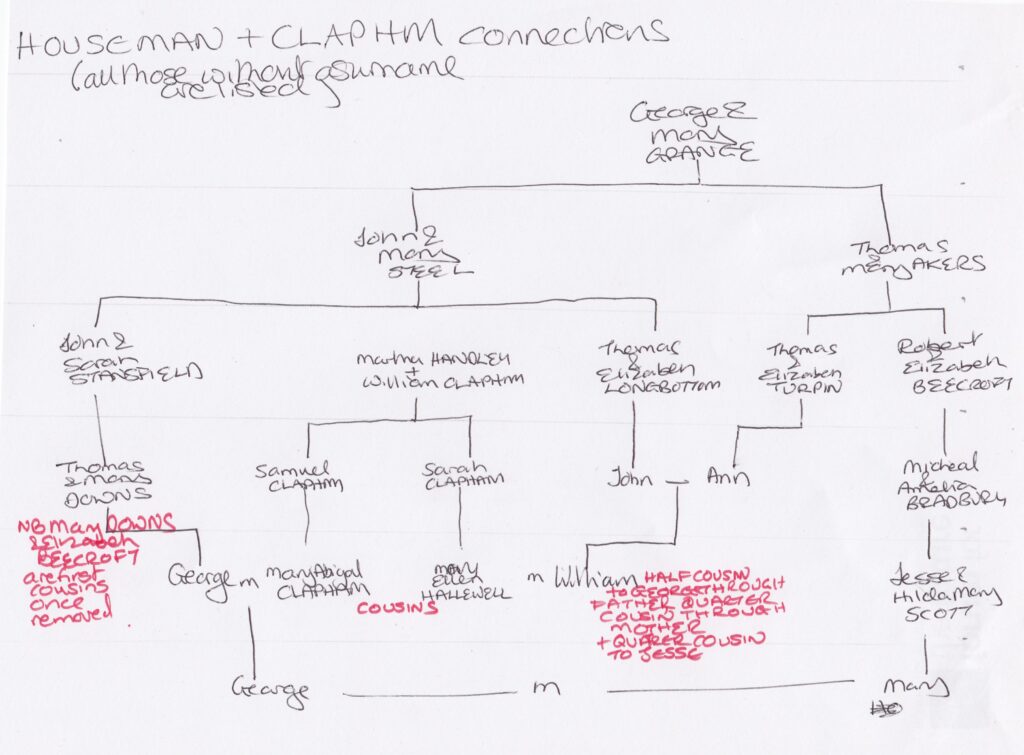

In 1909, Mary Ellen married one William Houseman and moved to Felliscliffe looping right back into our family. It possible the two would have met when her cousin and my great grandmother Mary Abigail Clapham married George Houseman in 1906. William & George were both second cousins through William’s father, John Houseman, and third cousins through his mother, Ann Houseman. Incidentally this also makes William as closely related to Jesse Houseman, my Grandma’s father as it does to George, my Grandad’s father.

Although I have now identified Mary Ellen she was still absent from Martha’s 90th celebrations as she had sadly died the previous year.