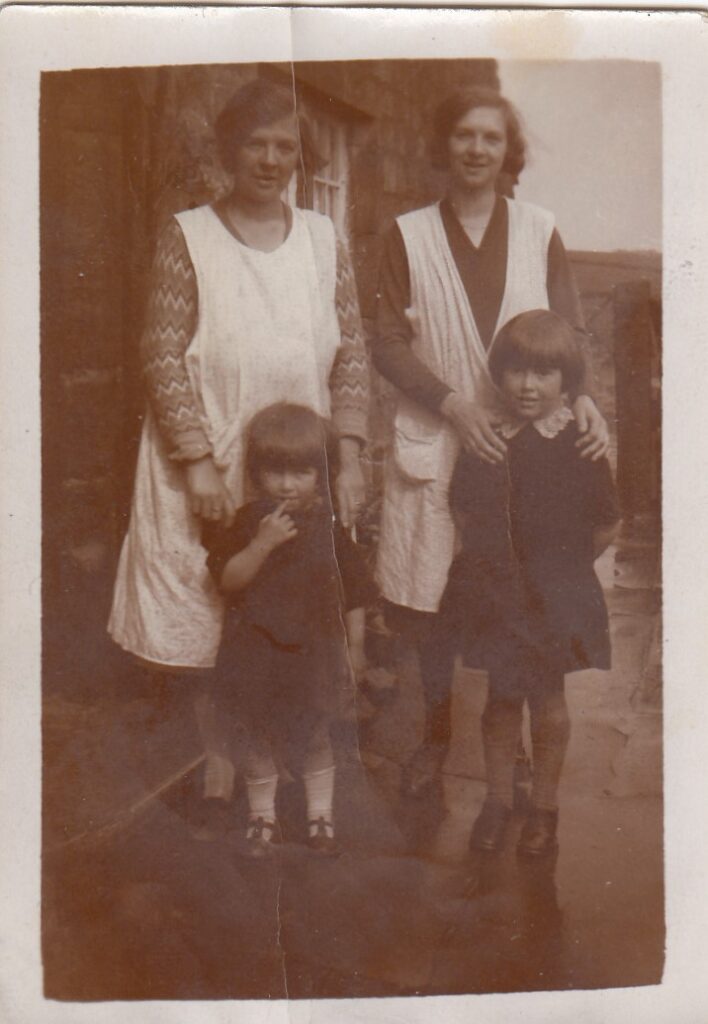

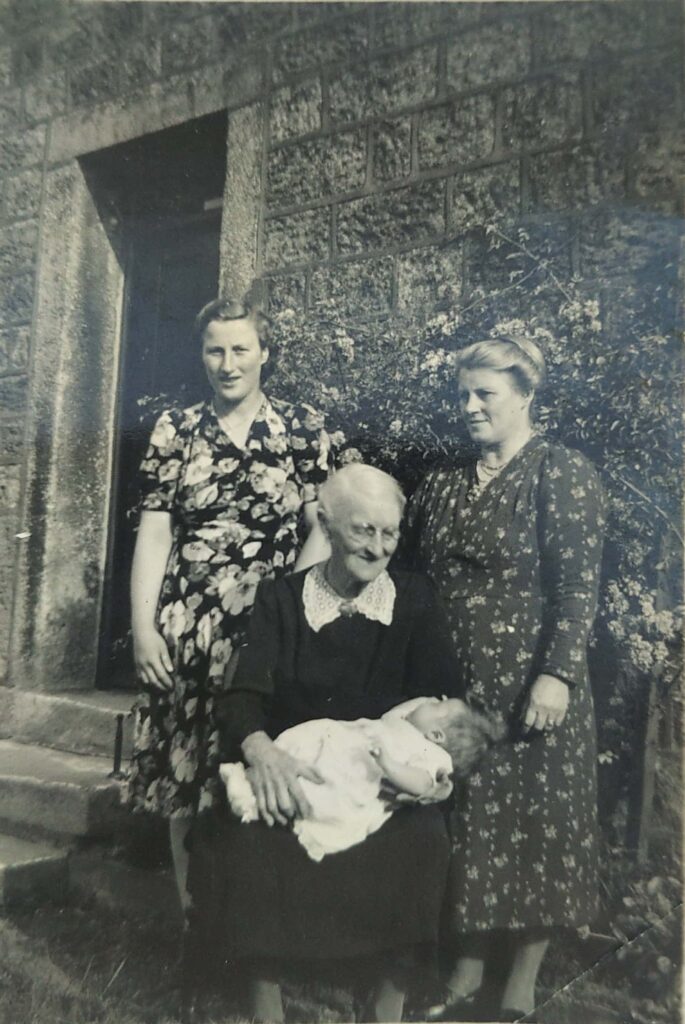

Christine Mary Houseman, Mary Houseman, Hilda Mary Scott & Maria Reynard

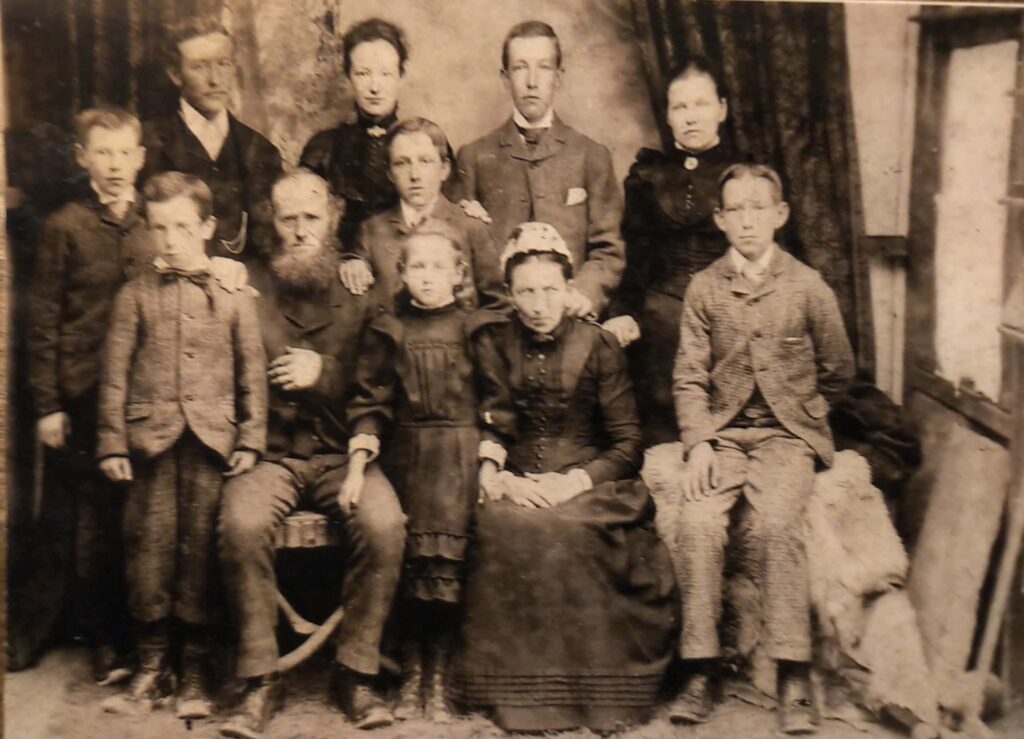

It was Christmas 2002. Grandma (my Dad’s Mum) was known for mostly standard presents, with an occasional inspirational one dropped, unexpectedly, into the mix. This year, it looked like a box of chocolates. I was gracious in my thanks and then I realised it wasn’t in a cellophane wrapper. I opened it up and inside was a photo album working backwards through my life and beyond, from that very summer to the 1940s. Right at the back was photo you see here.

I don’t know exactly why Grandma decided to do this. My best guess is that I was her eldest grandchild and was two years married. I think, perhaps, she was looking to inspire a new generation.

I have loved this photo since I have first seen it. It is August 1947 outside Prospect Farm, Lindley. My Aunt Christine is the baby, her mother, my Grandma, her mother, Hilda Mary nee Scott, Grandma’s mother, my great grandmother and finally Maria nee Reynard, Hilda’s mother and my great, great grandmother. A fellow family story blogger shared their three Grandma photo and story last week and made me want to share this story. It’s a super brief summary of four “mothers” that I plan to share much longer stories about.

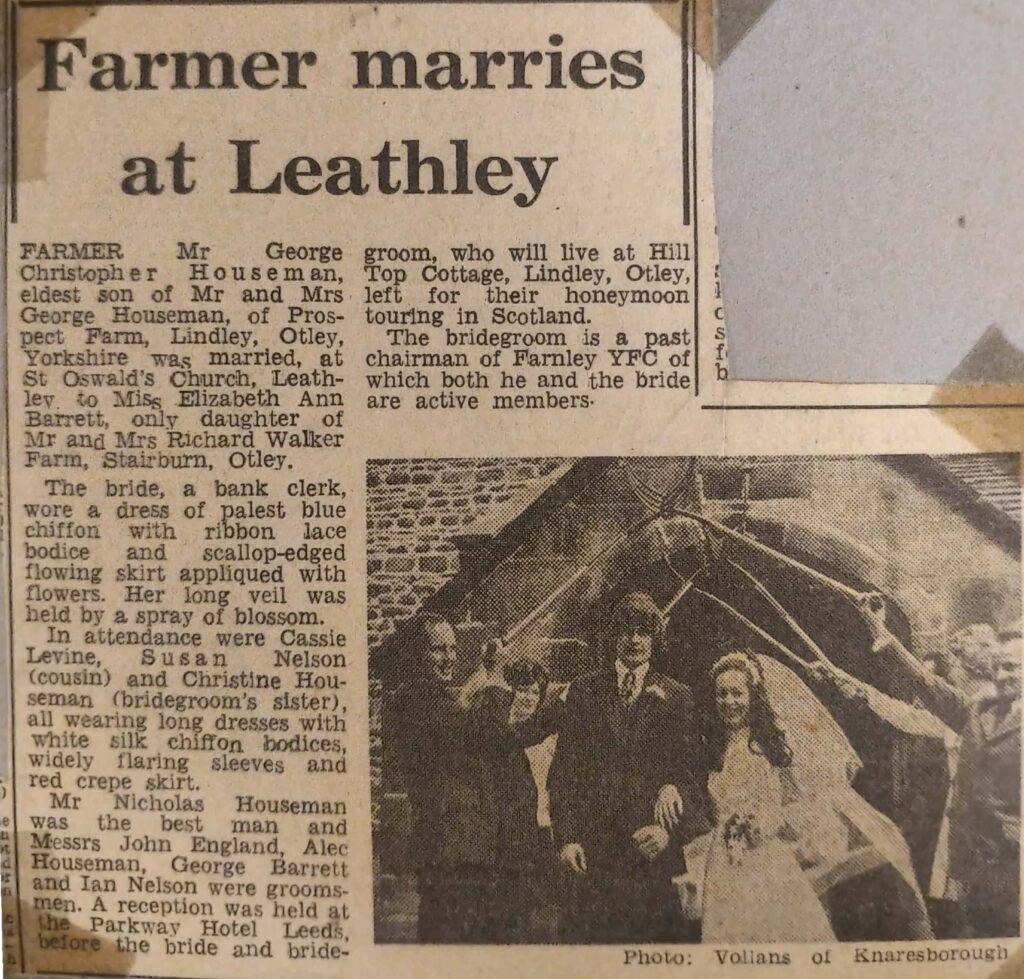

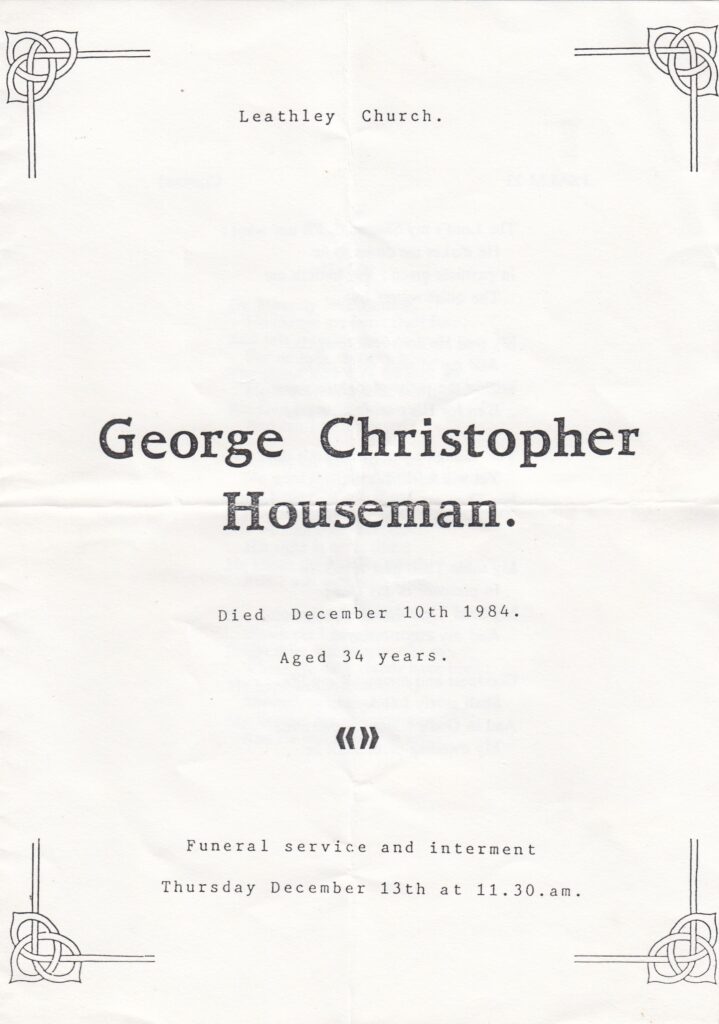

Christine Mary Houseman, the baby in the photo, is a very special person in my life. She was born on 13 June 1947. Her older brother, George Christopher, lived just two and a half days, so she was de-facto oldest child. I always got the sense she was encouraged to stay at home, the daughter who would look after her parents. Whether this is true or not, Christine never married. She was a farmer, a caterer, a WI produce judge and a Sunday School teacher at Norwood Bottom Methodist Chapel. Her twin loves that I witnessed were Young Farmers and us, her nieces & nephews. When my Dad, her brother, died in 1984, she was a constant support. The best epitaph for me, though, came many years later when talking to some ex-Young Farmer friends, who said “We still ask ourselves what Christine would have said” – she was as important in their lives as she was in ours. Sadly, Aunty Christine lost her battle with cancer on 1 April 1999.

Mary Houseman, the new mother, my Grandma, was born in 1921. This being the 100 year anniversary of her birth I plan to write a more fulsome story. She married my Grandad, George Houseman, in 1945. This photo, though, tells something of her life. It’s taken on the front doorsteps of Prospect Farm, Lindley. Grandma moved here when she was a young child. She left, briefly, when she married and had returned by the time of this photo. As she writes it

“One Monday when Thomas [Grandad’s brother] and George [my Grandad] went to Otley auction they had been talking to my Dad and he told them that George Baxter had got other work as an apprentice joiner in Otley. That just left Dad, Mother and George Barker to start hay time. Would we consider coming back home and taking over the farm? They would find somewhere else to live as soon as they heard of something near and suitable (what a decision for us to make). It was coming back home for me BUT I was now married and felt that I could not please both my husband and Dad. It was harder for George to leave home where he was born and Thomas at the face of hay time. What had we to do? Mother told me that Dad had been so sad and lost without me at home. He was not the only one. Meg my little dog from being a pup just whined and wouldn’t do anything for anybody else. Thomas and George had been to look at other farms previous over the past but never found anything that they liked. So we decided it was an opportunity not to be missed. We came back home to live here at the beginning of July.”

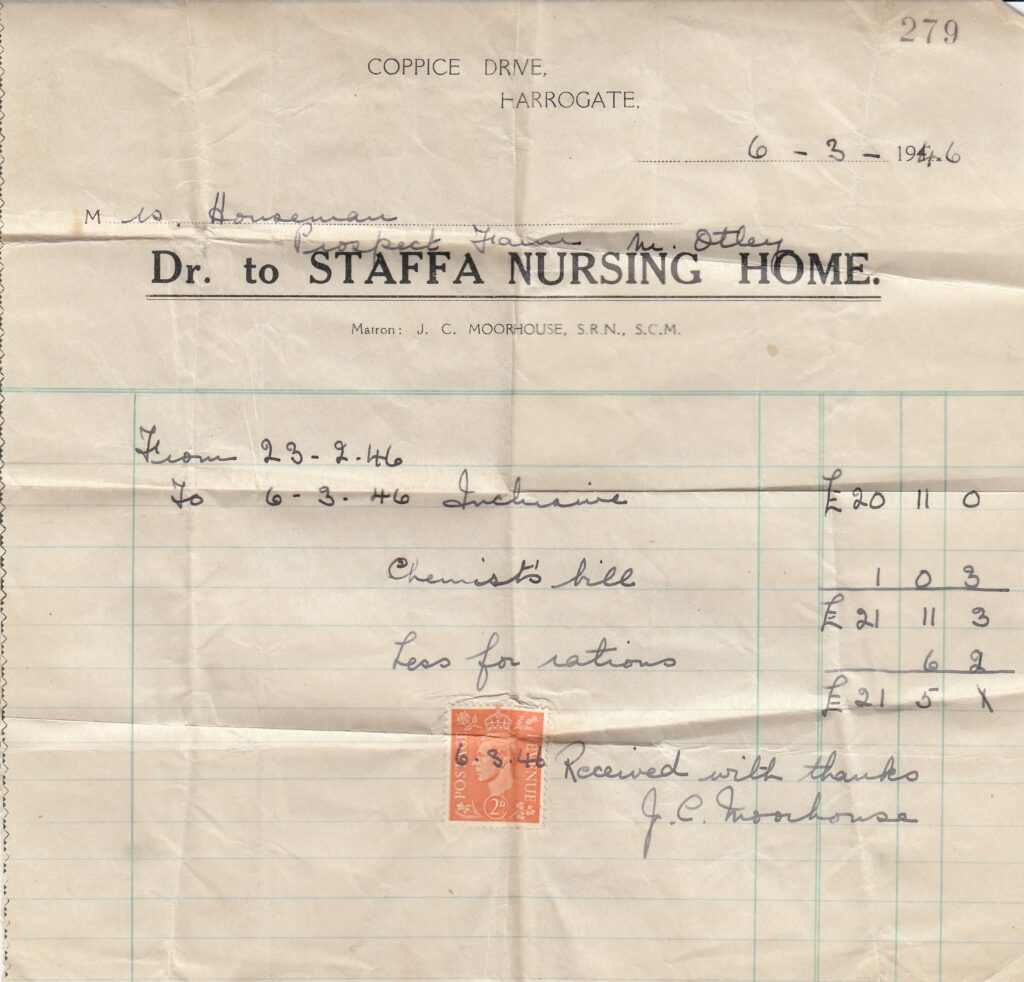

We have photos of Grandma and her own great grandchildren on her 90th birthday just a few steps away from this photo. Grandma didn’t leave Prospect Farm until she was too ill to live without full time specialist nursing care. She died on 31 March 2020 aged 98.

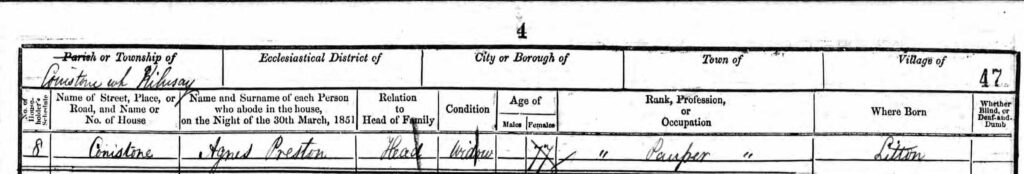

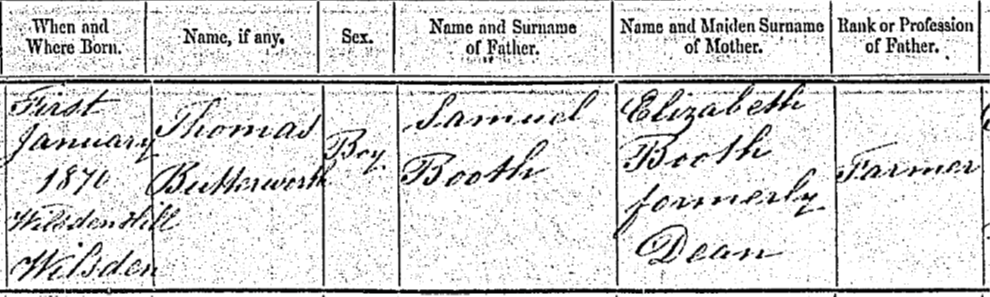

Hilda Mary Scott is stood to the right of the photo. Hilda was born on 31 August 1891 and grew up in Pickhill near Thirsk. She was a beautiful young woman who knew her own worth. She married Jesse Houseman on 28 September 1915 and moved, originally to Haverah Park and then to Prospect Farm. Everything I have read suggests this was a love match, like the postcard from Jesse to Hilda that reads simply “Dear Hilda, hope you are keeping alright, it seems very queer without you. Love from Jesse.” Hilda & Jesse had three daughters, Muriel born in 1916, Jessie in 1918 and my Grandma, Mary, in 1921. She was a champion butter-maker, competing and winning in a number of local shows. Her death on 9 August 1954, of cancer, left her family heartbroken.

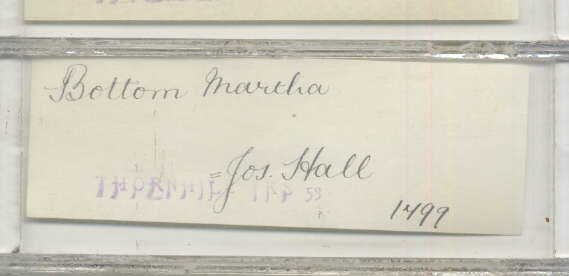

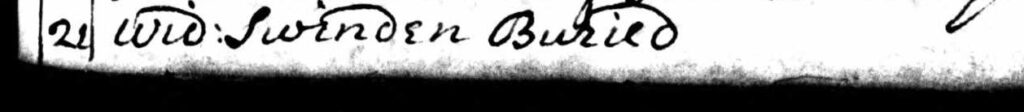

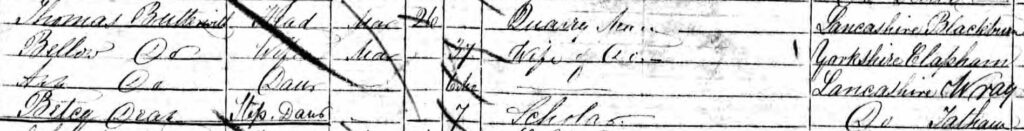

Maria Reynard sits at the front of the photo. Maria was born on 16 December 1861, daughter of Mary Ann Gill & William Reynard. She married John Scott in 1885 and together they had eight children, Hilda Mary being the third child and first daughter. The family prospered moving into a detached property, Prospect House in Pickhill, that John had built. By the time this photo was taken, Maria, 85, was already a great grandmother several times over and yet she still looks delighted to be holding baby Christine in her arms. You can read more about Maria’s family photo album and her son, Walter Scott.

Four generations captured together in love and motherhood.

With much gratitude to my Aunt Christine, my Grandma, Mary, my great grandmother, Hilda and my Great Great Grandmother, Maria, in who’s arms the generations have been nurtured, to Joan Weise who’s three Grandma’s blog inspired this one and to Amy Johnson Crow whose 52 ancestors in 52 weeks challenge encouraged me to publish this series of stories.