Reader warning: what follows is a story of domestic cruelty and may be upsetting to some people. Domestic abuse still happens today. Any woman (or man) who experiences this deserves all our support. The citizens advice bureau provides an excellent list of those who you can contact for help whether you are male, female, straight, gay, young or old. Please reach out.

This story has also been published on A Few Forgotten Women.

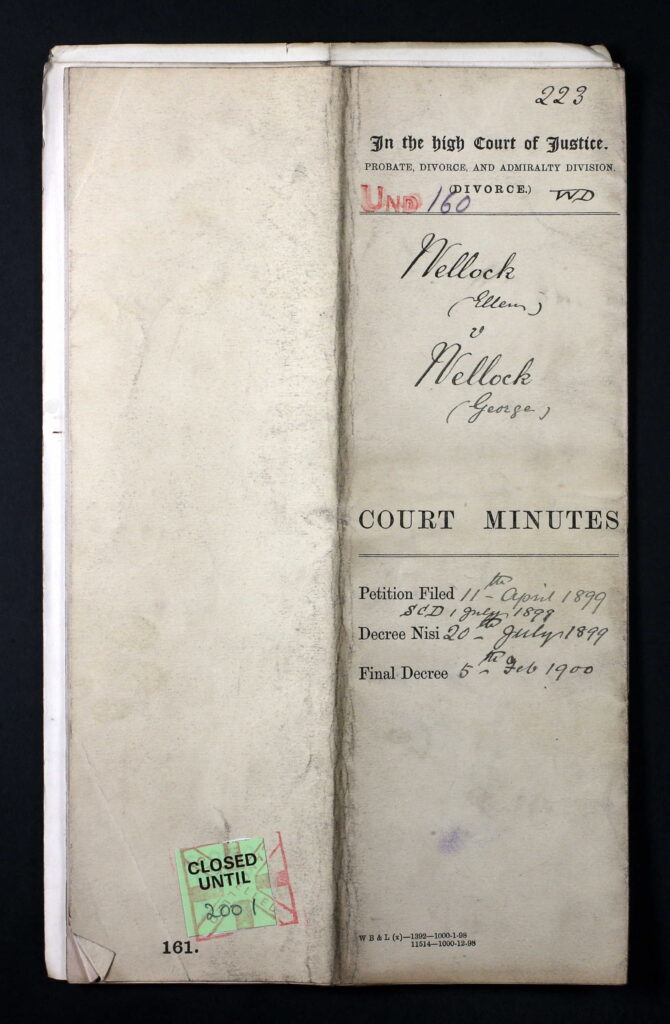

This is the story of how a young woman from Yorkshire, Ellen Richmond, succeeded in divorcing her violent, abusive, adulterous husband, George Wellock, in 1900.

“George Wellock was guilty of habitual cruelty…through his continued cruelty your Petitioner had a miscarriage on two occasions….seized your Petitioner by her neck, knocked her against the wall and threatened to jump on her and deprive her of her life and at the same time he struck her violently on the face and arms several times…apprehended…on a charge of committing indecent assault upon a young girl named Pollard”

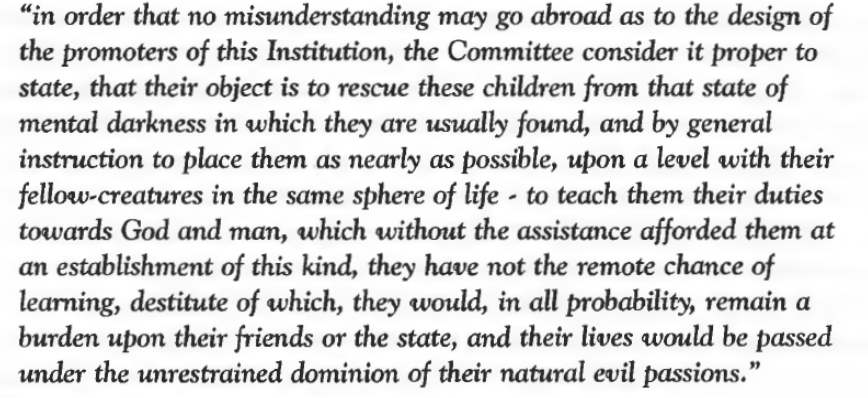

Thus reads the 1899 petition for divorce by Ellen (Richmond) Wellock. Yet these horrific descriptions of domestic abuse were insufficient support on their own for Ellen to obtain a divorce without also providing evidence of the husband’s adultery, proof that George was to inadvertently provide through his own defence in the trial for the “indecent assault upon a young girl named Pollard”.

A brief history of divorce

First a brief canter through the history of divorce. Prior to the Matrimonial Clauses Act of 1857 divorce could only be granted by way of an Act of Parliament, passed by both houses. Unsurprisingly it was both rare and hugely scandalous. It was also almost always brought about by the man. Just four of the 324 cases of divorce granted prior to 1857 were requested by women, none of which resulted in a happy outcome. (It’s well worth reading this piece by Amanda Foreman).

Post 1857, women gained the right to petition for divorce through to do so, unlike men, they needed to prove not only adultery but some other fault such as cruelty, rape or incest. They also had to have the necessary resources to travel to London to attend court, stood an extremely high likelihood of losing custody of any children and of course, as women were deemed to be chattels, left the marriage without any assets. The annual number of divorces stood at something under 300 at this point.

The Married Women’s Property Acts of 1870 & 1882 were important staging posts. Proving divorce was still as arduous, but at least the woman stood a chance of obtaining custody of children and holding onto some of the assets she may have brought to the marriage. By the late 1890s the annual number of divorces had crept above 500, 40% of them brought by women.

According to the office of national statistics, 512 divorces were granted in 1900 of which 209 were brought before to court by women. One of these courageous, ground-breaking, women, Ellen Richmond, was somehow connected to our Wellock family, not once, but twice.

The cousins

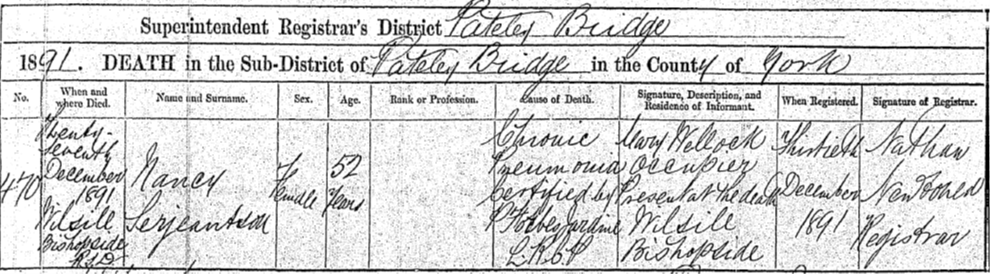

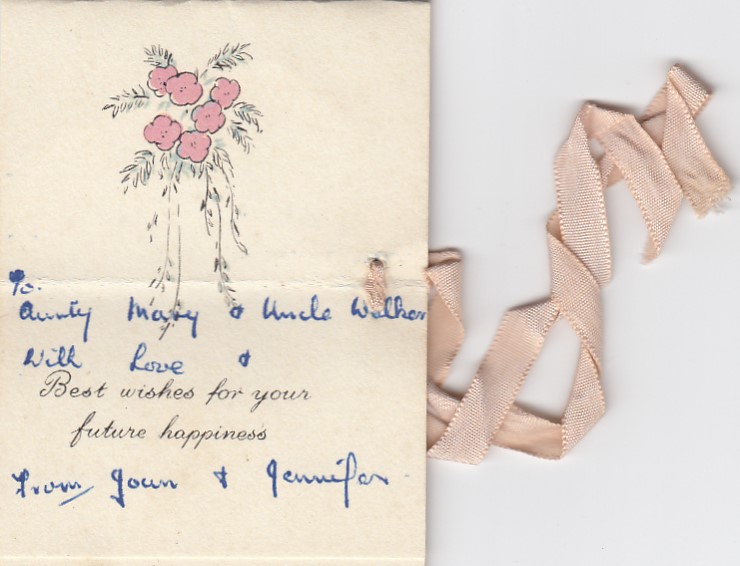

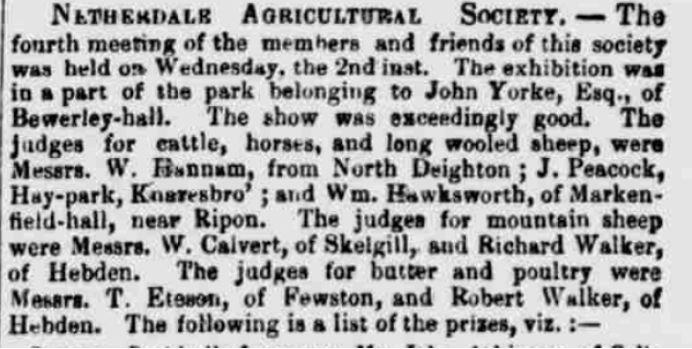

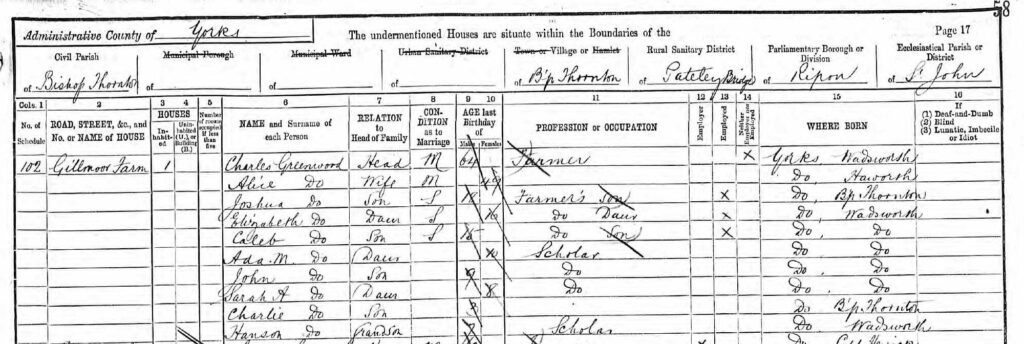

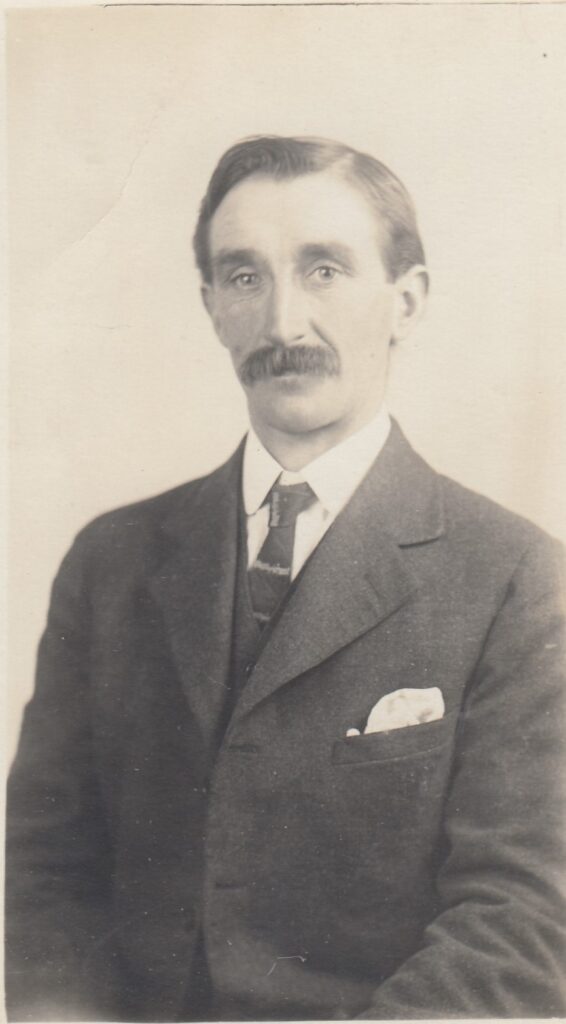

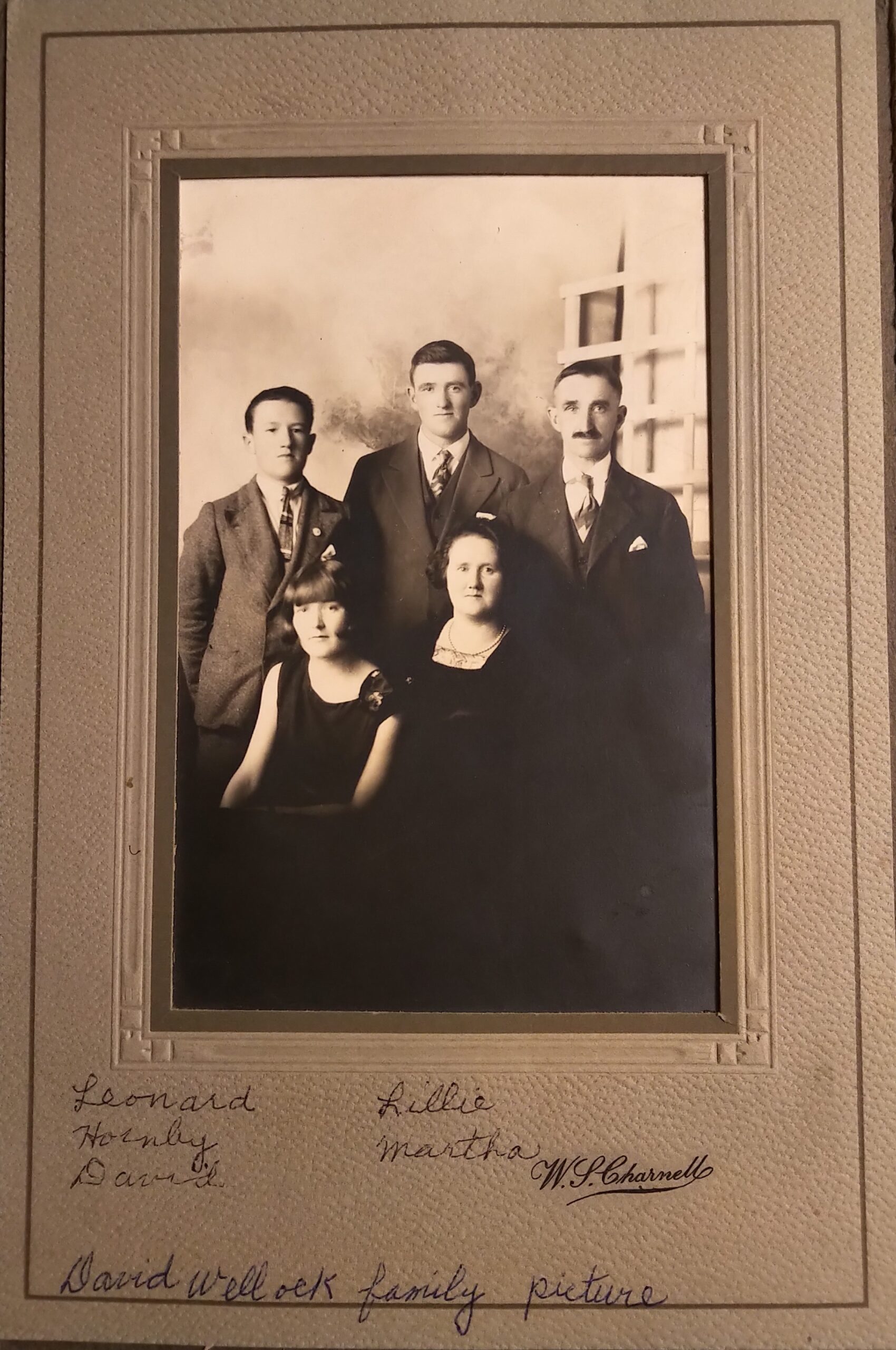

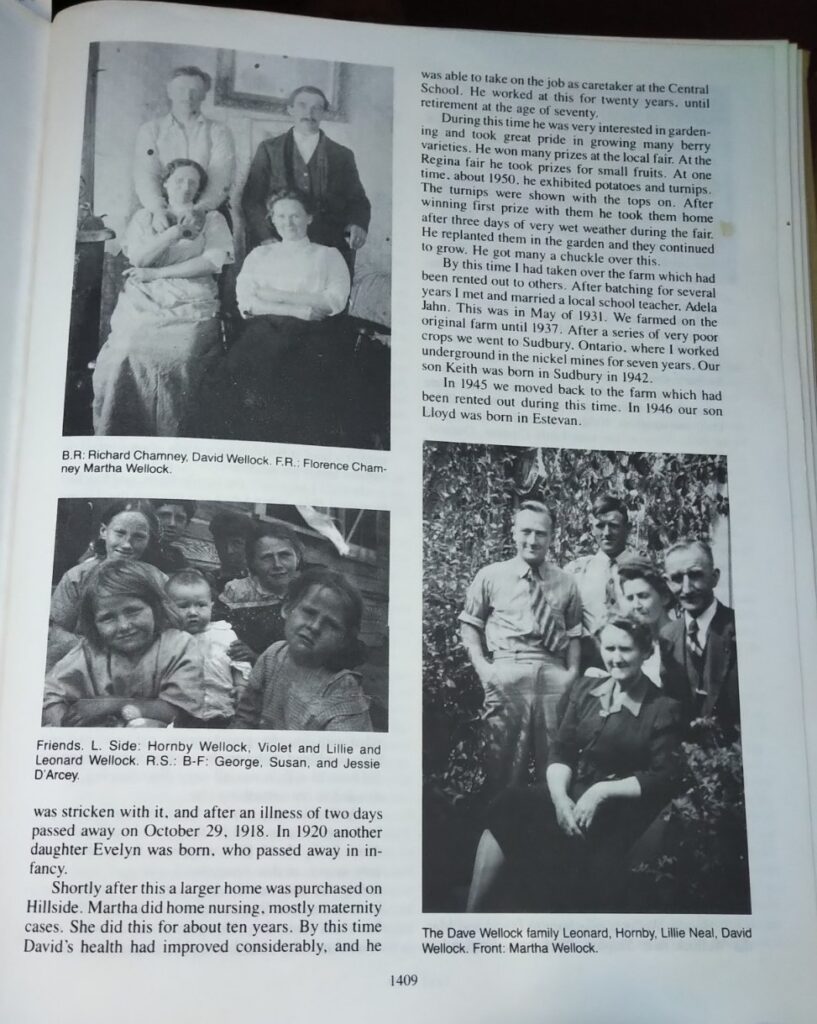

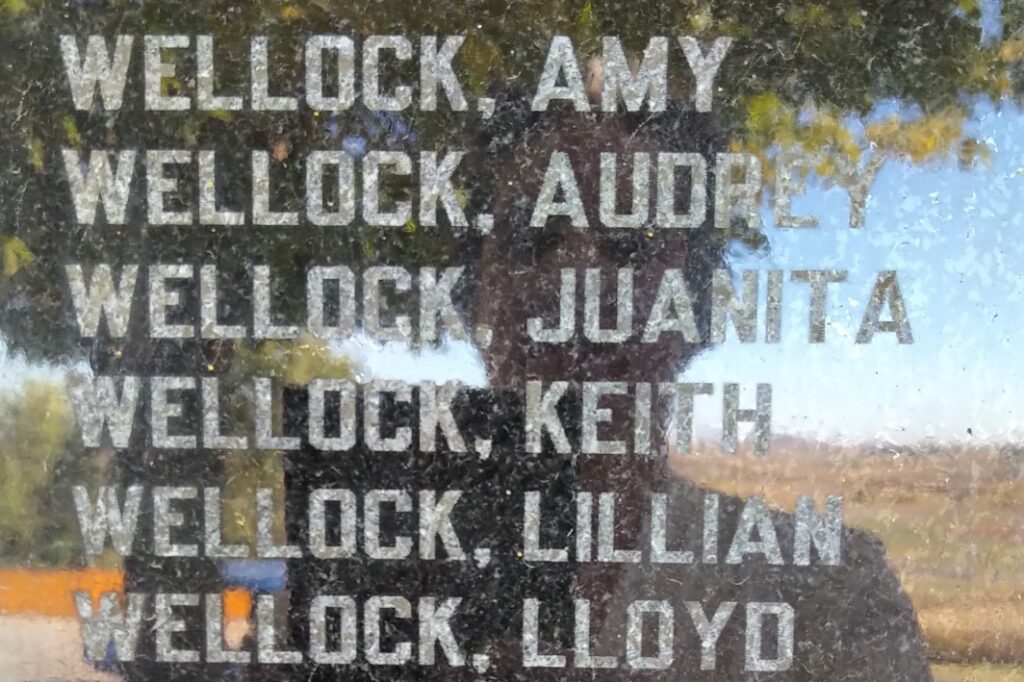

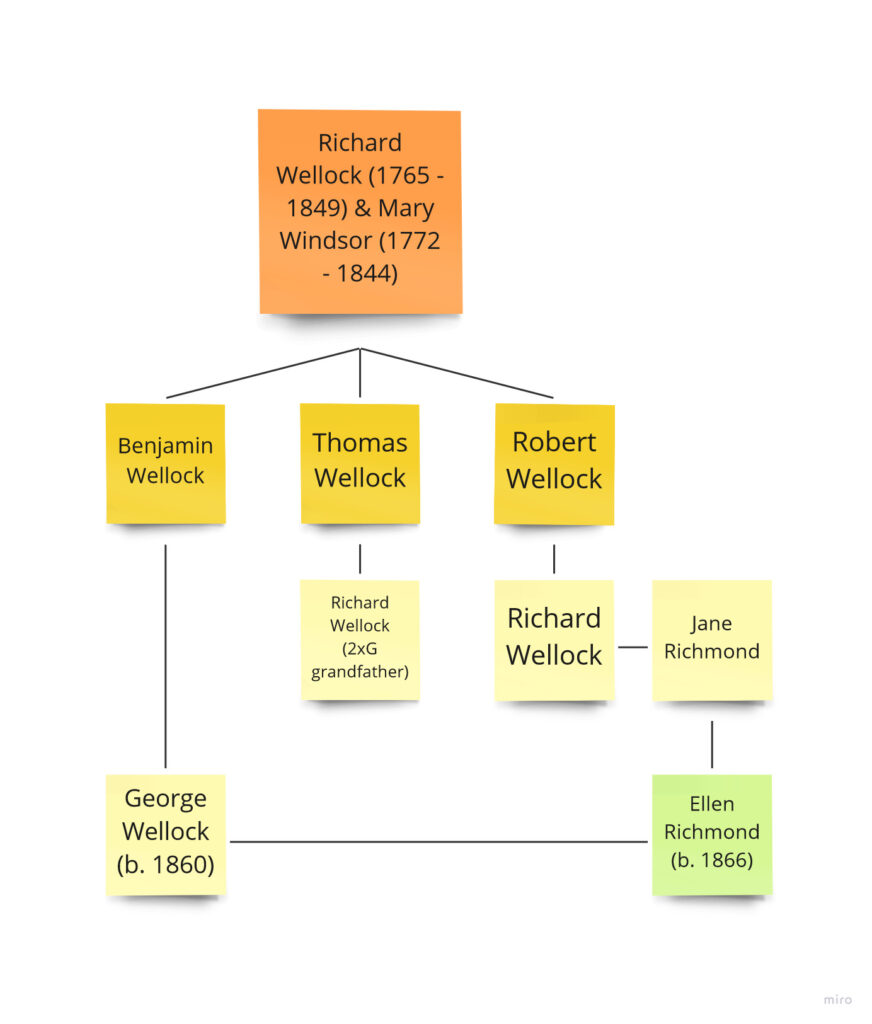

The story starts with three cousins. The role of my own great, great grandfather, Richard Wellock, is simply to provide a connection to the other two cousins through his father, Thomas, the ninth child of my 4x great grandparents, Richard Wellock (1765 – 1849) and Mary Windsor (1772 – 1844). Richard & Mary had eleven children over a twenty-eight-year period (as an aside Mary really deserves a medal). Benjamin (1802 – 1867), the sixth, was father to the above-named George Wellock, Robert (1817 – 1902), the youngest child, was father to Richard, stepfather (and possible biological father) to one Ellen Richmond.

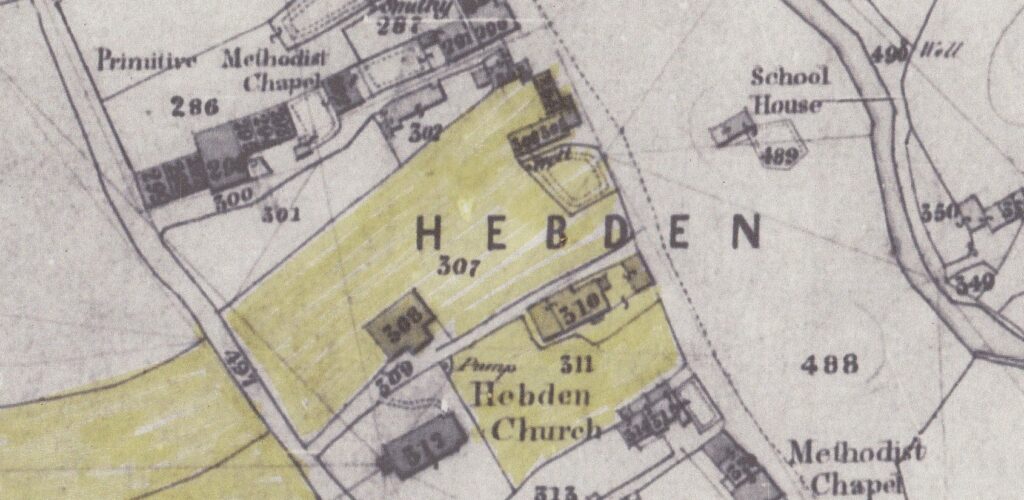

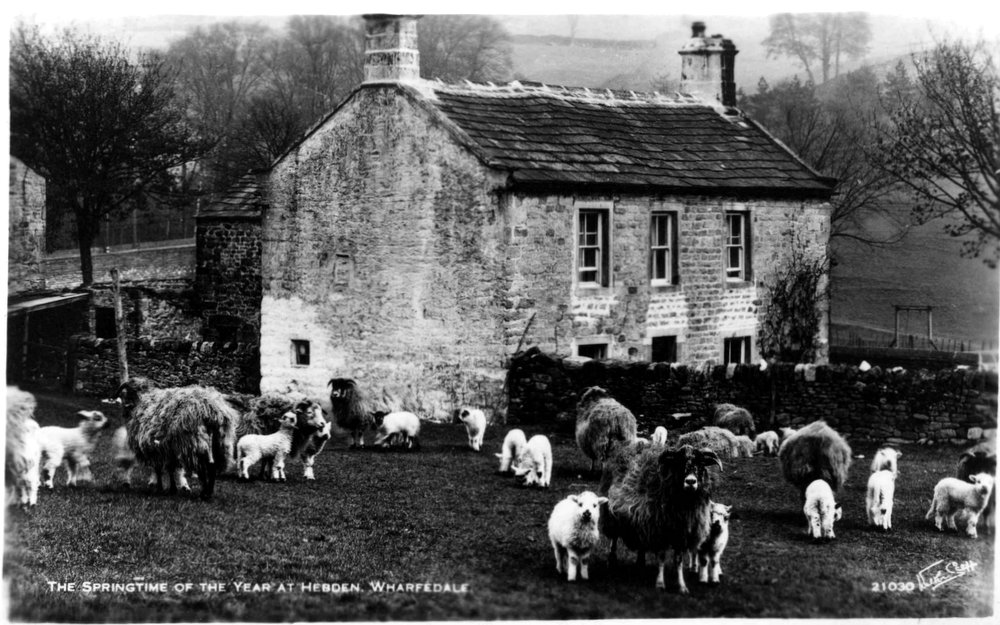

My 4x great grandparents, Richard & Mary, faced a bit of an embarrassment of riches. Of their seven sons, at least six survived to adulthood and had children of their own (as did two of their daughters). Blame the healthy Craven air. In this instance it seems that the family farm at High Garnshaw passed from Richard to his youngest son, Robert, and then onto Robert’s youngest son by his second wife, Jenkinson Wellock. Benjamin & Thomas had to make their own way, as did their nephew Richard (Ellen’s stepfather) but whilst Thomas found a farm high up in the dales, Benjamin made his way closer to Bradford via Calverley, setting the scene for what followed.

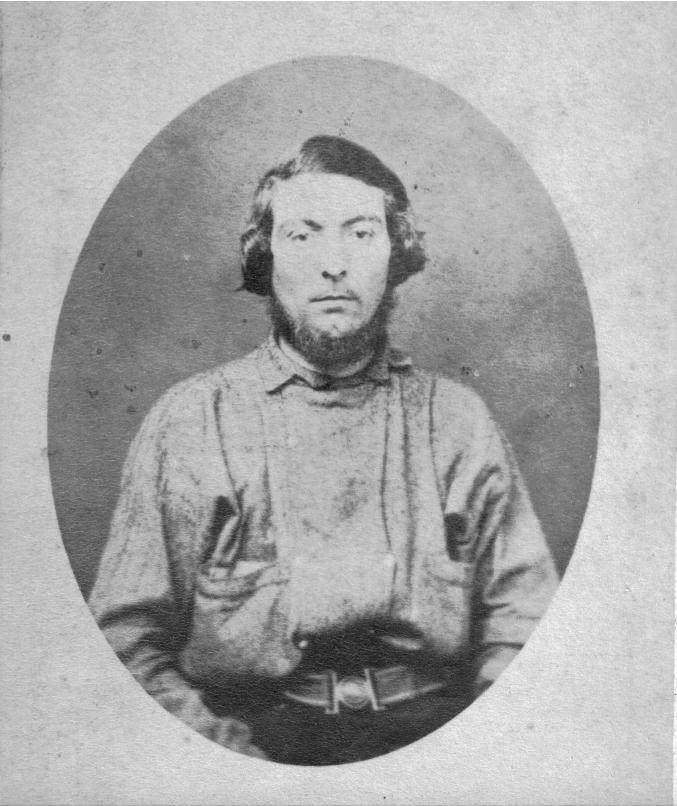

Benjamin married late, aged 38, to Margaret Calvert, a woman seventeen years younger than he. George was the baby of the family, born in 1860, when his father was already 58. Whilst he had sisters closer in age, his youngest brother was eleven years older than he which I expect made him a coddled baby. That was until his father died in 1867. Whilst Margaret kept the farm running through the 1871 & 1881 censuses (no doubt with the help of George) life would have undoubtedly become harder. I can speak from my own experience of the impact losing a father before you are ten can have although thankfully none of us has chosen violence as an outlet.

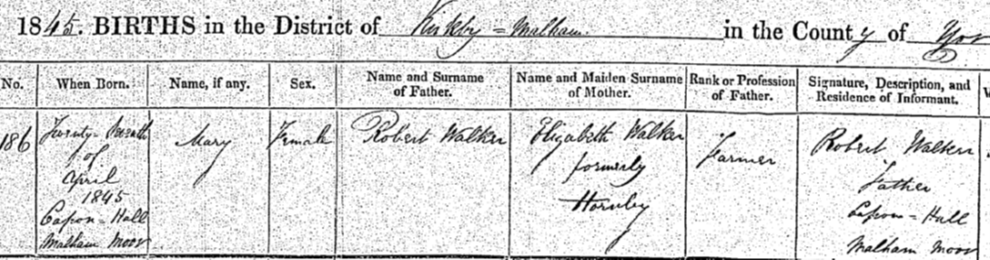

Let’s get back to Ellen. She’s not without her own “family history.” Born on 28 February 1866 in Ramsgill, it wasn’t until several months later that her mother, Jane Richmond, married Richard Wellock (the cousin). Whilst Richard always treated Ellen as his own daughter (she is described as such in the 1871 & 1881 censuses) the gap between birth and marriage would suggest he wasn’t the biological father as does the lack of any further children. (Childless marriages in the 1800s always intrigue me and Jane herself had already proved fertile leading me to presume the infertility was down to Richard). Ellen was a special only child.

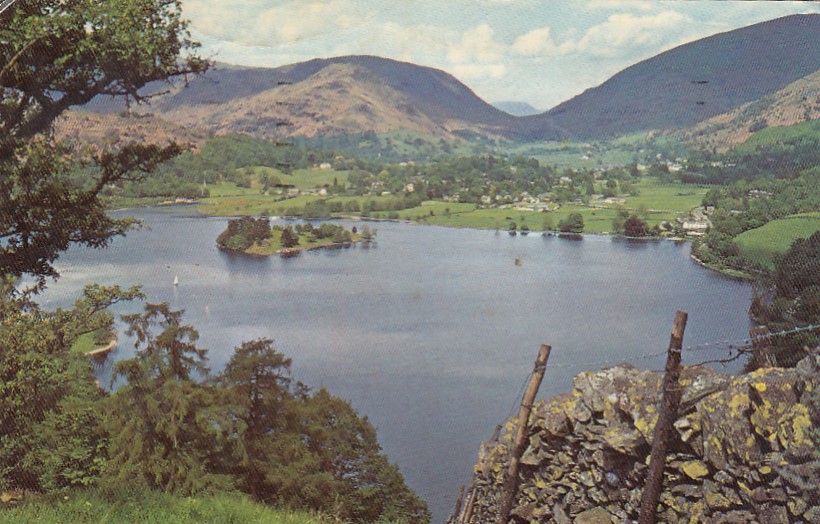

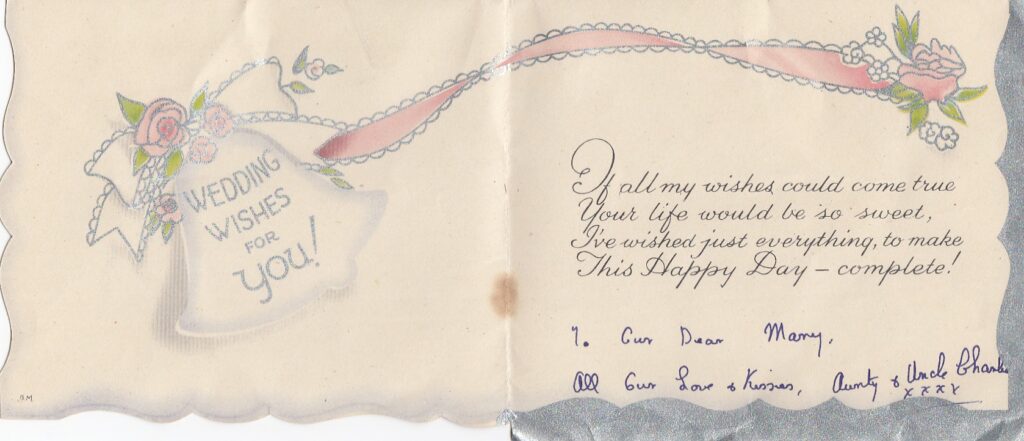

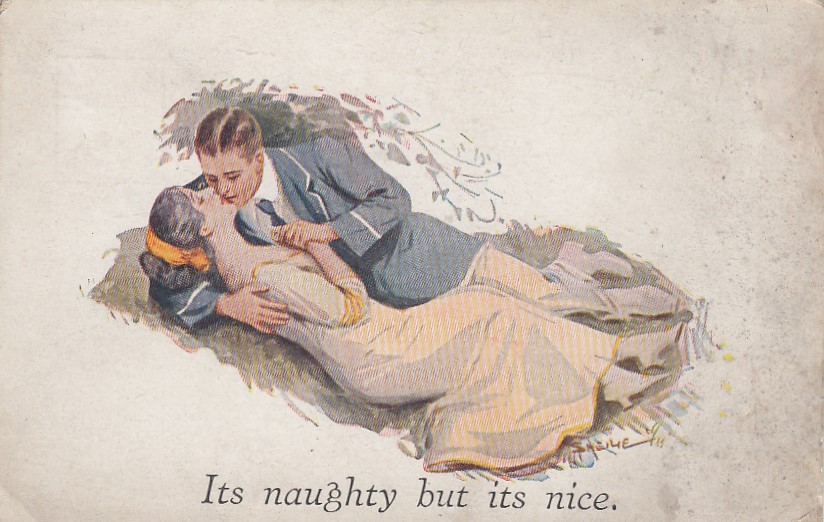

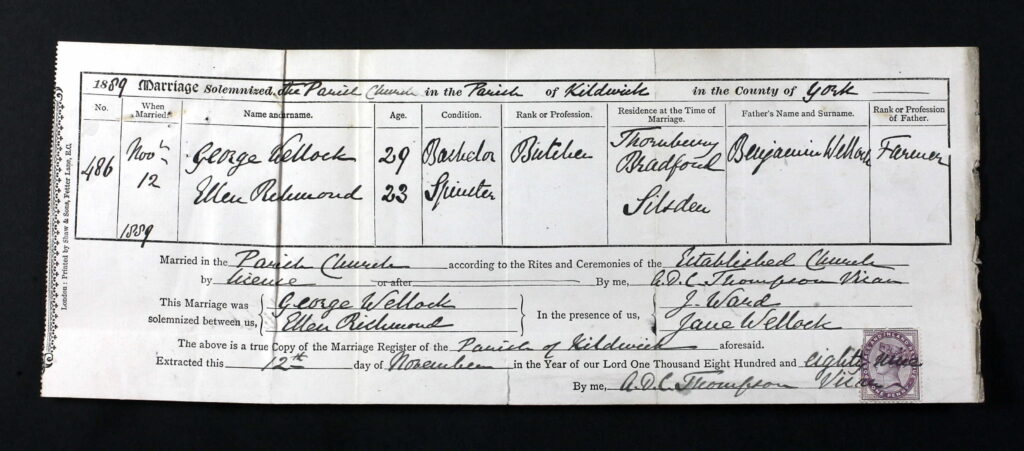

Ellen & George would have met at a family gathering. She, the protected, impressionable (and possibly spoilt) woman charmed by an elder cousin who had a way with women & already knew the ways of the impossibly metropolitan city of Bradford. Was it years of dancing at family parties or a short whirlwind romance? Who knows. Whatever the circumstances, Ellen was smitten, and they married at the beautiful ancient St Andrews of Kildwick on 12 November 1889.

Which, according to Ellen’s petition, was the day on which her life as the only beautiful, protected daughter came to a violent, abrupt halt.

The couple’s first baby, Edith Ellen Richmond Wellock, arrived safely on 17 January 1891 and was duly baptised on 27 January 1891 at Laisterdyke in Bradford, her parents living at 31 Thornhill Terrace, George working as butcher. Ellen then suffered two miscarriages as a result of George’s violence, before the arrival of Mabel Jane on 7 February 1894. Mabel Jane is baptised at Eccleshill on 28 March, the baptism record noting the family’s place of residence as 99 Killinghall Road a few minutes’ walk from Thornhill Terrace.

The cycle of violence, pregnancy, violence and miscarriage may well have continued had George not also been a serial adulterer.

Late in 1894, George flirted with a young woman called Clarissa Crossland in his butchers shop, followed her home and didn’t return for a week. Next George met a woman called Pollard with whom he frequently cohabited between the end of 1895 & 1896.

By July 1896 the violence was escalating. Ellen had been forced to flee from the house to the relative safety of a neighbour and on 30 July, George threatened to kill her with a carving knife.

The following day George left, perhaps realising he had gone too far. He moved to Colne, changed his name to George Calvert (using his mother’s maiden name) and took up with a woman named Lizzie Stansfield. Ellen took her two daughters back to the safety of her parents’ home at Cragg Top Farm in Silsden.

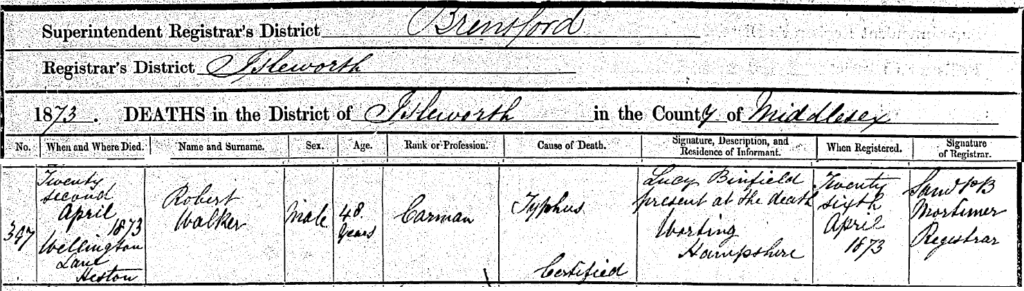

This might have been the end of the matter had George not assaulted a young woman called Mary Elizabeth Pollard in February 1899. Mary was the daughter of the woman George had previously cohabited with. This time he was arrested (at the house of Lizzie Stansfield) and charged with indecent assault. He was eventually convicted of “just” common assault (of an underaged girl) and sentenced to six weeks imprisonment, the judge noting that he was “not strong enough to put to hard labour.”

During the trial George had chosen to defend himself. I had thought this was down to money, but Anna Maxwell Martin’s recent WDYTA show suggested that a man might choose to do this simply to continue his cruelty – forcing the woman to submit to angry, manipulative questioning. George claimed the charge was a “put up job” because he had been cohabiting with Mrs Pollard. Suddenly Ellen had the evidence she needed to demonstrate adultery.

Albert Victor Hammond was an influential solicitor in Bradford, the founding partner of the law firm Hammond Suddards (now part of the international firm Squire Patton Boggs) against whom, co-incidentally, my sister & I used to play football in the late 1990s/early 2000s. Together with Wynne Baxter & Keeble of 9 Laurence Pountney Hill, London, they took Ellen’s case to court.

Yet even the trial was to test Ellen’s courage as in 1899 divorce cases were all held at what is now the Royal Courts of Justice on The Strand in London.

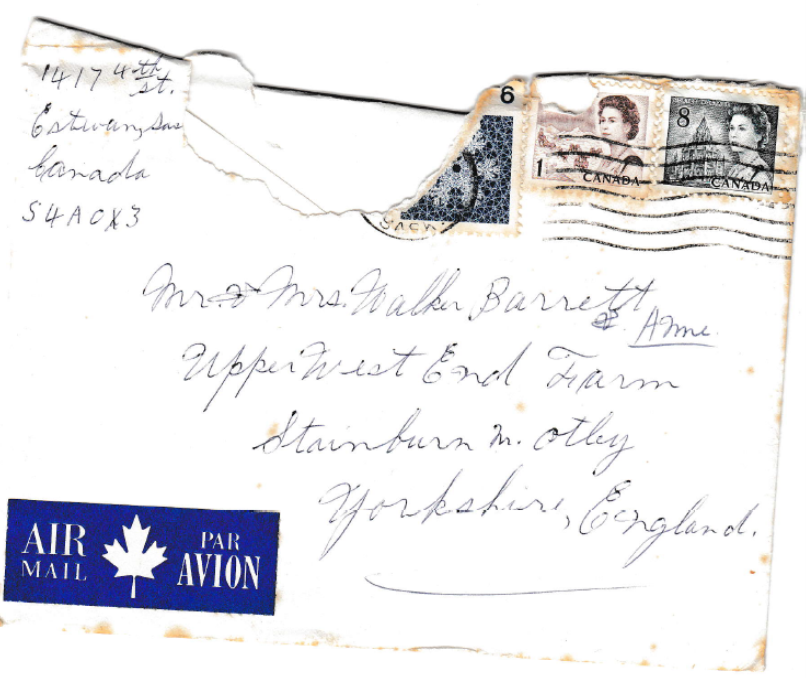

First Ellen faced a trip to London. By 1900 London was home to 5 million people, the capital of an empire. Even today I often provide a bit of advice for rural friends daunted by their first visit to the capital on where to stay, what to eat and how to get around. Ellen was unlikely to have known anyone.

Second there’s the court itself. Again, I know from personal experience how intimidating this place can feel with it’s grand entrance packed full of barristers dashing through with arms full of papers. Even with current signage it took me a while to find the room where the appeal in relation to my husband’s death was being held. I was glad not to be on my own.

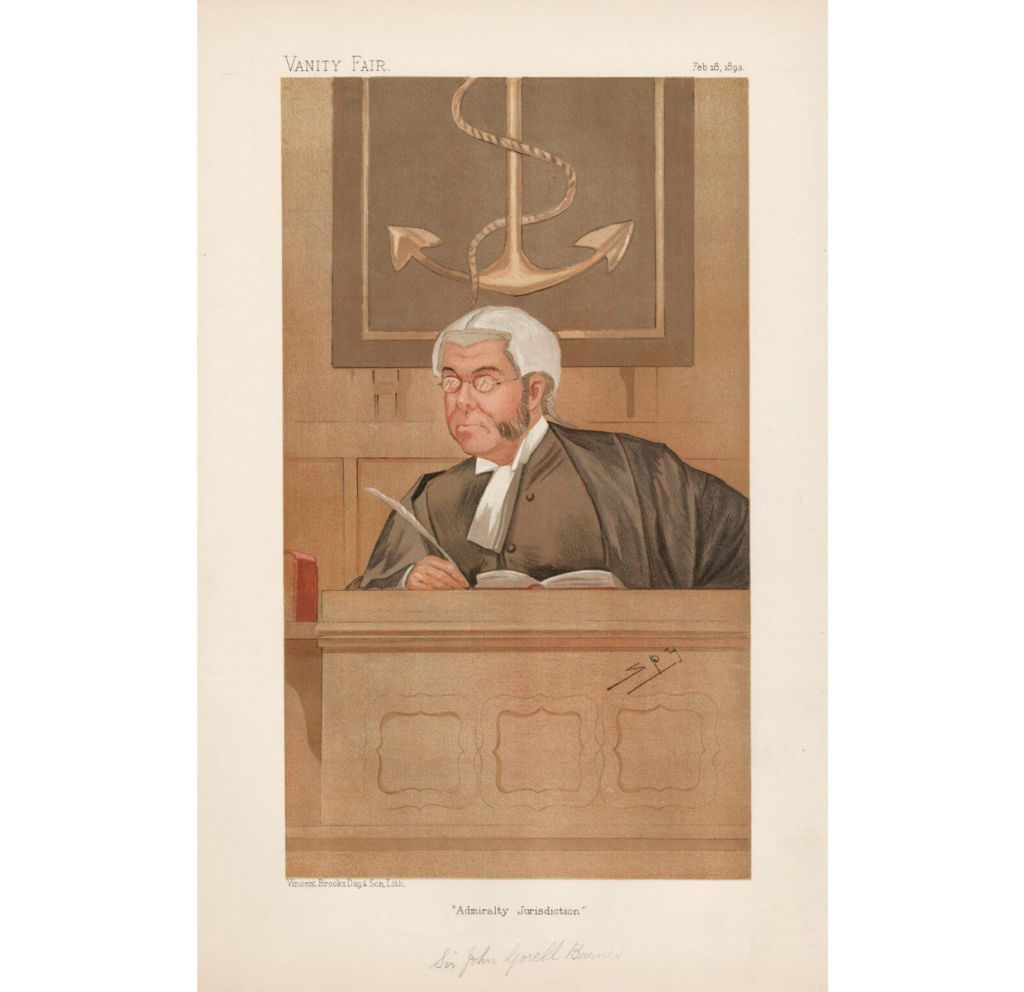

Finally, there was the judge, Sir John Gorrell Barnes, who presided over the case. In his wig and gown, peering down from the judge’s chair, he would have terrified all but the most worldly and privileged of petitioners.

Yet the thought of gaining her freedom from a violent, abusive husband, must have sustained Ellen throughout.

George chose not to turn up and so the decree nisi was granted on 20 July 1899.

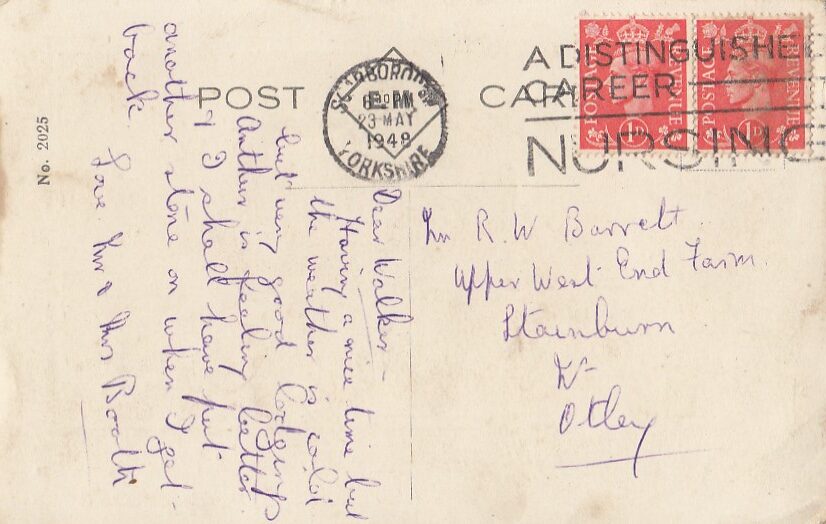

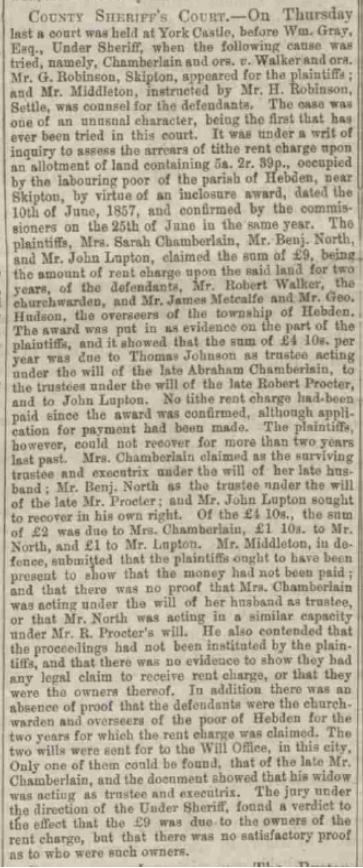

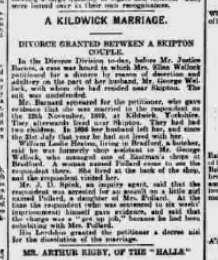

Of course, this was not the end of the ordeal for Ellen. Divorces were rare and still made the papers. Not just one paper, in Ellen’s case, but four, ensuring full coverage across both Yorkshire & Lancashire with the news being published even before Ellen had returned to Yorkshire. What’s more the papers mentioned only desertion and adultery as if the violence Ellen had suffered was unimportant. Such were the views of the time that many people would have thought Ellen to blame for not being able to keep her husband satisfied.

The following year, on 5 February 1900, the decree absolute was granted and Ellen was finally free.

The other woman

George too, was free, and just six weeks later on 19 March 1900, he married the aforementioned Elizabeth Stansfield, calling himself a bachelor and not a divorcee.

Lizzie Stansfield has her own back story. An illegitimate child, her mother went on to a childless marriage to a Martin Stuttard, then travelled to America, had another illegitimate child Lewis Pratt, before returning to England to live with her daughter. George & Elizabeth had one son together and also appear to have raised Lewis who worked as a butcher’s assistant and died in WW1. I hope Lizzie fared better than Ellen for, unlike Ellen, she did not have a family to support her.

Ellen’s remaining story

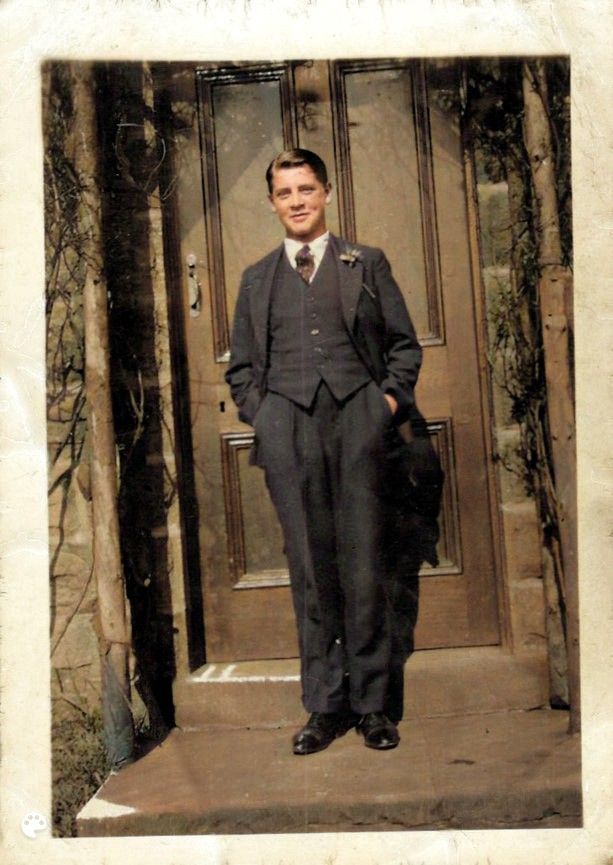

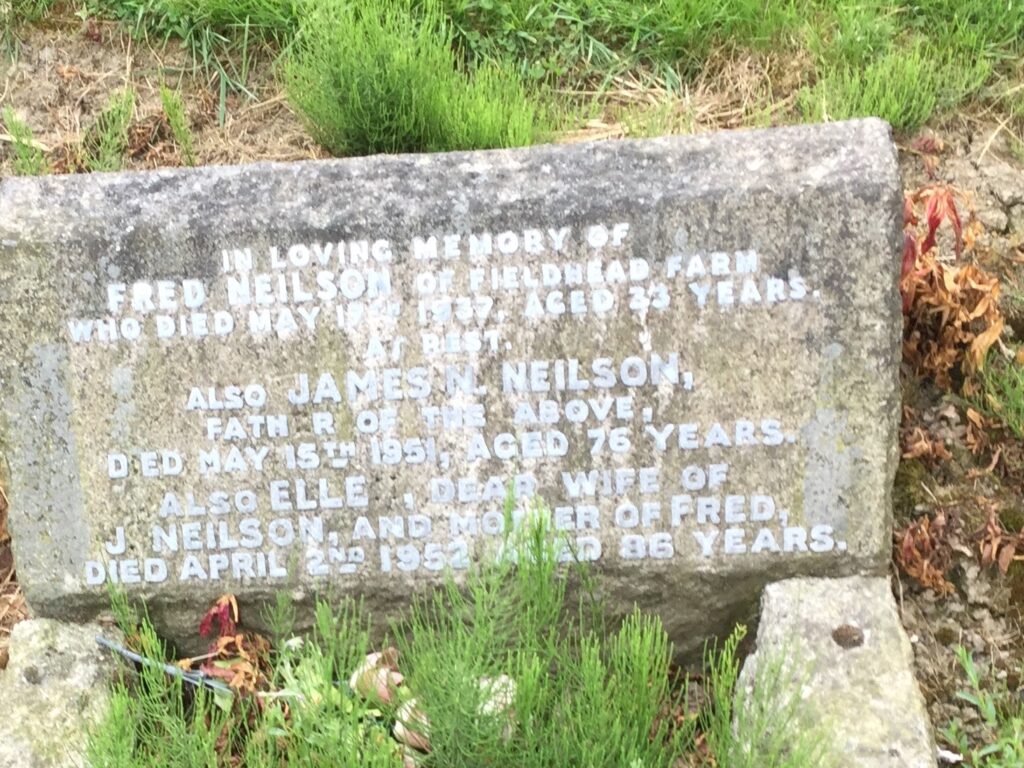

Ellen became a housekeeper before marrying a younger man from Scotland, James Neish Nielsen, in 1903.

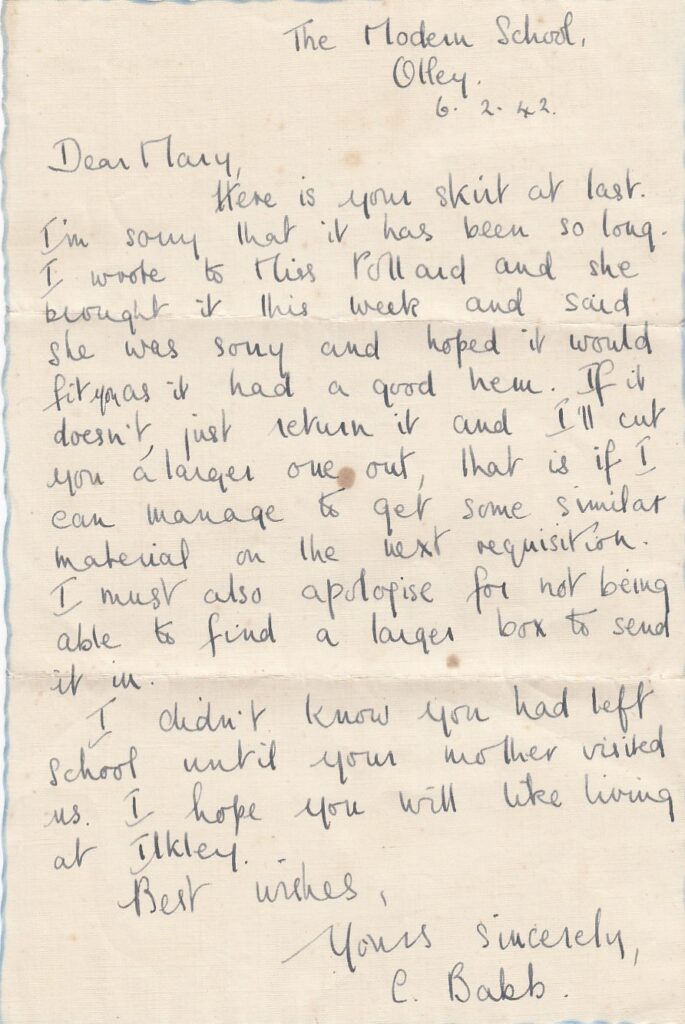

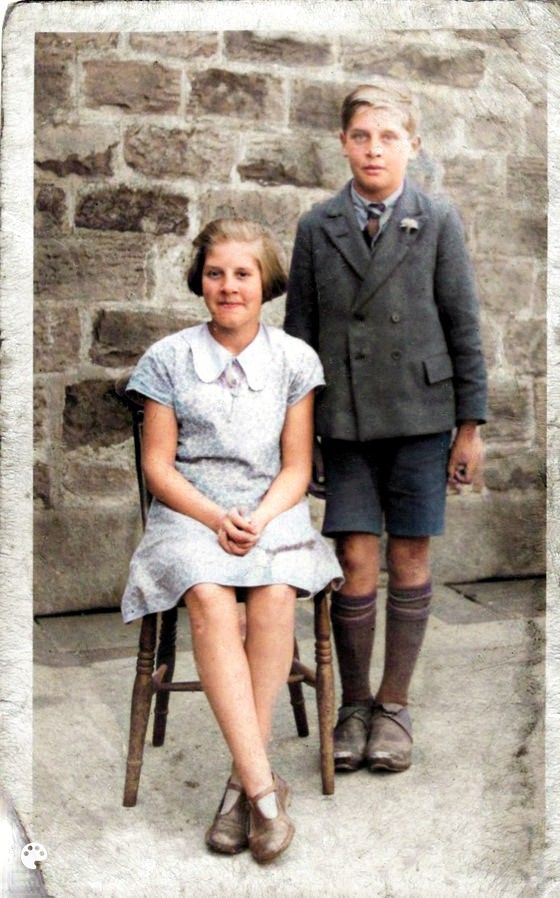

The two daughters too fared well. Edith, the elder, married locally and had two sons and whilst the second of these died as an infant in 1932, the first went onto to have a family of his own. Mabel became a schoolteacher and a renowned educationalist, travelling the world to learn and to speak, eventually dying, unmarried, at the age of 81 in London.

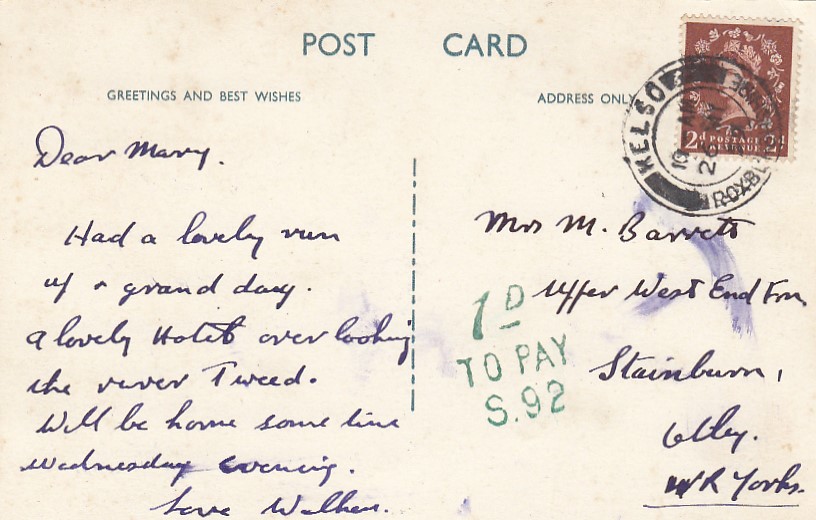

Whilst the second half of Ellen’s life was not without further tragedy (James & Ellen’s second son, Richard, born in 1906, died in infancy and their first son died in 1937 aged 33) the relationship at least seemed a much happier one captured in the description “dear wife” on her memorial stone when she died aged 86 in 1952.

I think Ellen deserves more appreciation for the courage she showed over the course of her first marriage and divorce in part paving the way for others to hold abusive partners to account. I hope this blog goes some way to recognising this. With much gratitude to Ellen & her parents.

Whilst this is a story of Ellen’s courage, as much as it is of George’s violence, I understand that the content could be disturbing for living descendants. From online research I believe that both Ellen & George have living great grandchildren, but none who carry the Wellock surname and I have not used any of those newer surnames to avoid anyone making the connection. However, if you are a descendant and wish me to redact any part of this story, please do get in touch.