There are so many reasons to be proud and grateful for being born a Yorkshire lass and whilst I suspect that there aren’t many people who would put the Yorkshire Parish Register Society on that list they have proved absolute gold dust in helping evidence the depth of our Yorkshire roots.

Founded in 1899 the aim of the Yorkshire Parish Register Society was to transcribe and publish at least one volume of an original parish register every year (complete with indices, an absolute godsend). It came as no surprise to discover that the first volume concerned St Michael-Le-Belfrey, possible the primary church in York (minster excluded). As the introduction explains:

“The City of York is rich in Churches, and consequently in Parish Registers also. These cannot fail to be interesting to a large number of Yorkshiremen, because many of our County families sprang from amongst its citizens, and many of the junior members of other families of distinction, in the country, were brought up and followed their professions or callings here. As the capital of the north, also, York was the resort of many persons in the highest stations of life, from all parts of the Kingdom, so there can be no town in the county, and perhaps in the Kingdom, London excepted, in which the Parish Registers can equal, in interest, those of York”. Yet these parish registers are the most egalitarian of history books recording rich & poor, men, women & infants alike (almost, as mothers are for more rarely referenced) allowing us to trace, recognise and amplify our ancestors whatever their station and gender. The single mention in a parish register of of “Wid Swinden, pauper”, my 7x great grandmother even inspired a poem. Given our ancestors were agricultural labourers, tenants of a few acres or a yeoman at best there is little evidence of their existence. We were rarely poor enough to require a record of relief and never wealthy enough to for others to write about. Yet the parish registers have enabled me to trace several lines deep into the 17th & even 16th centuries.

Volume V (published 1900) & XVIII (published 1903) concerned the parish of St Michael’s & All Angels Church, Linton in Craven, faithfully transcribed in two parts by the Rev. F. A. C. Share. M. A. then rector of Linton. Thanks to the Rev. Share (and at least one other Wellock descendent) I have long since been able to trace my Wellock line back 450 years to one Robert Wellock, father of William Wellock, who was baptised his son in this very church in 1574.

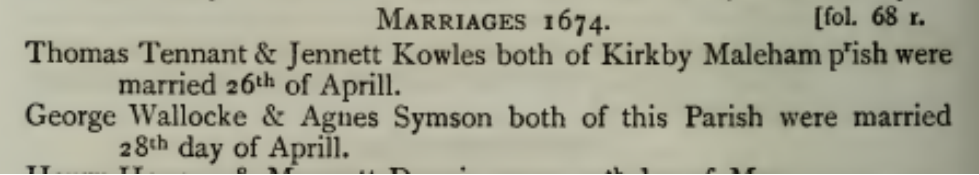

This is where Agnes Symson, our 8xg grandmother crops up, apparently apparating into the parish of Linton-in-Craven, just in time for her marriage to George Wellock (Wallocke) on 28 April 1674. Whilst the Wellocks are well documented, their wives haven’t been accorded the same attention. In reviewing the original record, I was struck by one simple phrase “both of this parish.”

The hunt was on.

Reviewing the registers suggested two possible candidates for her father, James “of Garneshaw” and Robert “of Hebden Moor.” Fortunately Robert was quickly eliminated as “Agnes the Dau : of Robert Symson of Hebden Moor side baptized the same day, viz: 6to March [1663/1664]” would not have been old enough to marry in 1674 and ensured that Robert would not have had an older Agnes, at least not one who survived childhood. (As an aside, I am reasonably confident that Robert & James must have been brothers with a mother named Agnes as it was not that common a name.)

I also knew that Agnes & George were also described as “of Garneshaw” in their children’s baptisms. This was looking promising.

James appears numerous times in the register: in 1639 when he married Isabel Rathmell and in 1651 when Isabel is buried, in the baptisms of Margaret (1640), William (1645), Ann (1646), Thomas (1656) and Mary (1662), in the burials of William (1646), John & Mary (twins buried in 1651) and John (1661) (where he is named as father) and of his second wife Mary (1681) as well as his own burial on 18 November 1684. If James was such a regular attender of church (at least so far as baptisms, marriages and burials were concerned) why why was there no baptism for Agnes?

This is where I am again grateful to Rev. Share[1] for his commitment to the task at hand extracting every last detail he could where records were in poor condition. I was struck by the following two entries.

…ghter of James Symson……in ye townshippe….borne ye last day of December, baptized ye 80 of January following [1653/1654]

[here follow. fragments of about a dozen baptisms ; only these Christian names are left, viz. : Margret, Elizabeth, Thomas, Agnes, Henry, and Isabell.] Wm Perte of Griston Hall yeat b…..d ye..th day of March. A……of….Knight…..rneshaw was borne the ….day of March 55 [sic]………[follows on from 4 October] [1655/1656]

Despite the obvious connection between “Agnes” and “rneshaw” I felt confident in ruling out the second entry as James’s son Thomas was born on 4 June 1656. Which left me with “…ghter of James Symson.” This had to be Agnes.

Here then, courtesy of Rev Share and the Yorkshire Parish Register Society, is Agnes’s story.

Agnes Symson was born on 31 December 1653, a non-momentous day for most in that age, as the calendar was not to change for another century. Momentous though for her mother, Mary, being the safe delivery of her first child. James, on the other hand, was doubtless hoping for a boy. Isabel, his first wife, had given birth to five children, Margaret (b. 1640), William (b. 1646), Ann (b. 1646) and then twins, John & Mary in 1651, but William & the twins had died as infants, the birth of the twins likely resulting in the death of their mother (Isabel was buried on 4 May, the twins were baptised on 11 May and buried on 17 December the same year).

Husbandry in these parts was not without challenges as these wonderful two entries illustrate: “Robert Holdgate of Garneshaw who was lost by a tempest of snow that fell the 3 day of January att night was found the 10th and buried the 11th day of the said January [1659/1660]” and “Septembr 17th 1673 happened a great fflood wch overflowing the Banke in the lower end of the Churchyard covered the most pt thereof below the Church. Burnesall bridge & Bolton Bridge & many more were driven downe by the violence of said fflood”. I’ve written before about Yorkshire snow, this can be a bleak and unforgiving landscape.

By 1674, James was getting on in life, likely in his late fifties or early sixties. Thomas, the only son James had not seen buried as a child, was still only 18, too young to take over the land. Agnes, then 20, may have been anxious when she shared the news of her forthcoming pregnancy, but, in reality, this must have been seen as a blessing. George Wellock, 26, was the third son of a local farmer, trained from birth to run a similarly placed smallholding but without a tenancy to inherit.

So it was that Agnes & George started a Wellock connection with Garnshaw which, with some gaps, was to last over 200 years.

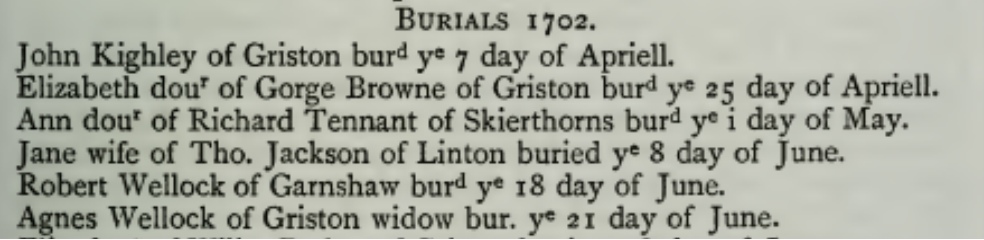

Agnes & George had four children: Robert (b. 1674) (Robert was baptised in August 1674, four months after the couple were married), Isabella (b. 1676) (named after James’s first wife?), Anne (b. 1683) and William (b. 1685) (our ancestor). The couple must have felt secure. Sadly, this was not to prove the case. George died in November 1694, leaving Agnes with four children aged between 9 & 20. It looks like Robert, then 20, may have been the one to take on the tenancy. Possible, not easy. Possible that is, until Robert, then aged 28, died in 1702, buried on 18 June in St Michael’s & All Angels churchyard. Agnes, then living nearby in Grassington, may well have come to tend her eldest son through illness, for she died and was buried just three days after Robert thus ending Agnes’s tale.

[1] Harry Speight in his book Upper Wharfedale, describes the Rev Share thus “Of Mr Share’s labours in the parish little now need be said. He is a hard and zealous worker, and I believe has never missed preaching a single Sunday since his induction to the living in October 1891. The industrious rector appears quite content with the 13,000 and odd acres of ground within his parish, and has sought no holiday nor other means of recreation than what this large expanse of mountain, moor, and pasture afford. He has lately copied for publication by the Yorkshire Parish Register Society, the important but ill-kept and in places much tattered registers of his parish, a work requiring the closes scrutiny and painstaking transcription”.